Prisoners’corpses are stacked on a cart in Gusen after liberation.

A schoolteacher, Sima Katz, the mother of three children, survived to tell the story of her encounter with ‘the great grave’: “At Lukiszki (Lithuania) we were kept outside for two days and then put into cells…at two a.m. the prison square was suddenly illuminated with floodlights. We were put aboard trucks, fifty to sixty women in a truck. In each vehicle there were armed Lithuanian sentries. The trucks headed for Ponary. We came to an area of wooded hillocks and were dumped among them. Still, the mind would not keep pace with reality. We were arranged in rows of ten and prodded toward some spot, from which came the sound of shooting. The Lithuanians then went back for more batches of people.

“Suddenly the truth hit us like an electric shock. The women broke out in piteous pleas to the sentries, offering them rings and watches. Some fell to the ground and kissed the sentries’ boots, others tore their hair and clothes – to no avail. The Lithuanians pushed one group after another to the site of the slaughter. By noon, when it became clear that there was no escaping this fate, the women fell into kind of a stupor, without any pleading or resistance. When their turn came, they went hopelessly to their death.

“Suddenly we saw a group of men [at Lutiszki]. At their head was an aged rabbi, wrapped in his prayer shawl; passing us he called out ‘Comfort ye, comfort ye my people.’ We were seized with trembling. The women broke into moans, and even the Lithuanians took notice. One of the guards ran up and hit the rabbi with the butt of his rifle. My daughters and I were on the ground. Other women did not wait to be led away but broke from the rows and went on. The rows were broken. The women sat down and waited for a miracle to halt the massacre. I had one thought in mind: to be among the last.

“Our turn came at five-thirty. The guards rounded up the remaining women. I felt my older daughter’s hand in my own…when I came to, I felt myself crushed by many bodies. Feet were treading on me, and the acrid smell of some chemical filled the air. I opened my eyes; a young man was sprinkling us with quicklime. I was lying in a huge common grave. I held my breath and strained my ears. Moans and sounds of dying people, and from above came the amused laughter of Lithuanians. I wished myself dead so I would not have to hear the sounds. Nothing mattered. It did not dawn on me that I was unhurt. A child was whimpering a short distance away. Nothing came from above. The Lithuanians were gone. The whimper aroused me from my stupor. I crawled toward the sound. I found a three-year-old girl, unharmed. I knew that if I survived, it would be thanks to her.

“I waited for the darkness to fall; then, holding the child in my arms, I wriggled up to the surface and headed for the forest. Not far in the interior, I came upon five other women who had managed to survive. Our clothes were smeared with blood and burnt from the quicklime. Some of us had nothing but our underclothes on our skin. We hid for two days in the forest. A peasant came by and was frightened out of his senses. He let out a weird shriek and fled. But he was not decent enough to come back and help us. He was sure that we were ghosts from another world.”

MASTERS OF DEATH

By Richard Rhodes

“When I close my eyes and think back, I can still see the SS guards in front of me. I still can’t comprehend how people can act that way. Essentially, they were very primitive people. They were animals. The SS men were most likely all good husbands and fathers. But when it came to us, they beat us, they hunted us down, and they murdered us. They didn’t hesitate at all before using their pistols. I just don’t understand how a person can be like that. The women were much worse. They were sadists. When we had to stand naked in Auschwitz, they used to talk to the men and laugh at us. At the time, I remember thinking, ‘My God, is this really happening?’ I felt so ashamed having to stand there naked in front of all those men. I couldn’t understand why the ground below us didn’t just open and swallow us up. You can’t imagine how degrading it is.”

VOICES FROM THE THIRD REICH

Steinhoff, Pechel and Showalter

In Kobersdorf [Austria] a pack of SA men attacked a 30-year-old rabbi, a Hungarian citizen named Goldberger. His entire property, everything that could be sold quickly, was confiscated. Later, the rabbi, his wife who had recently given birth, and three children – aged three weeks, a year and a half, and three years – were put on a truck together with the furniture left by the German robbers. They were brought close to the Hungarian village Harko. Three hundred steps away from the Hungarian customs official, yet still on Austrian soil, the SA men threw humans and furniture onto the street in the crudest way. The rabbi wanted to cross the border; yet, the Hungarian border control had to explain to him that according to new regulations, he was allowed to cross the border only with the permission of the Hungarian consulate in Vienna. Rabbi Goldberger had to shelter himself and his family from the icy cold and raging snowstorm in a small hut. This hut did not have a door but simply an opening with the wooden wall. He had to sleep the night on the muddy floor. People from the close by border town of Szopozn who had heard of the incident came to the border station with pillows and food. Yet, they were not allowed to see the rabbi, who was still located on Austrian soil. Again and again they were scared away across the border by the SA men.

After a few hours, three armed SA men ejected the rabbi from the hut with the words, “Get up, Jewish pig [Saujud]. Take your stuff on your crooked back and get out immediately.” The three SA men hit the rabbi with rifle butts. He suffered a broken rib, lying in his own blood. Meantime, the other SA men took away the blanket the children were lying on, saying, “Jew children should lie on the floor.” The rabbi hauled himself in the direction of the Hungarian border police, even though the Nazis continued beating him. He succeeded in reaching the border. Now the Hungarian border police had mercy and called for medical help from Szoporn [Sopron]. Rabbi Goldberger has suffered severe injuries. The children’s fingers and feet were frozen.

JEWISH RESPONSES TO PERSECUTION

By Jurgen Matthaus and Mark Roseman

Brutality at Majdanek [Poland] is perhaps best exemplified by Anton Tuman, the “Beast of Majdanek.” Carrying himself proudly and usually imitating a Napoleonic pose, Tuman struck fear in the hearts of the prisoners whenever he appeared. He flogged and beat them relentlessly. One day a female prisoner called out to her husband in the men’s sector. For the crime, Tuman ordered her to stand at attention for the day. At evening, he commanded the camp prisoners surround her, forming a huge square into which had been placed a flogging bench. Tuman tied the woman, naked, to the bench, and his henchmen flogged her until the pain caused her to lose control of her bowels. Laughing, Tuman kicked her and forced her to clean up her excrements with her hands.

Anton Tuman loved Majdanek. It was his camp and he cared for it with a zealous devotion. He would tolerate not the slightest deviation from the rules. For some infraction, he forced a group of prisoners to stand naked in the cold without food for three days and nights. Then he shoved the twenty-six men into the freezing water of the camp pool. They froze to death at once.

Extermination was big business at Majdanek. Rather than focusing on one process, the SS used several. In the first stages of the camp’s existence mass shooting was the major method…Mass executions often included several hundred or even a thousand victims. In addition to shooting, prisoners were killed by hanging. Each field had a gallows, and between Fields One and Two the staff erected a special facility with a row of nine hooks for collective hangings. Frequently the SS drowned inmates in the small reservoir. Others were strangled, beaten, or trampled to death. Many prisoners died from the living conditions in the camp.

HITLER’S DEATH CAMPS

By Konnilyn G. Feig

Members of the SS Helferinnen (female auxiliaries) arrive in Solahuette, the SS retreat near Auschwitz for a holiday. All were guilty of brutality and assisting in murder. Karl Hoecker (1911-2000) adjutant to the camp commander stands in the center. He served a mere six years in prison after the war and worked as a chief bank cashier until his retirement

[Poland] By October the order was for real. Placards announced that all Jews who did not go to the ghettos would be shot. The “shooting order” was made part of regular company instructions to the men and given repeatedly, especially before they were sent on patrol. No one could be left in any doubt that not a single Jew was to remain alive in the battalion’s security zone. In official jargon, the battalion made “forest patrols” for “suspects.” As the surviving Jews were to be tracked down and shot like animals, however, the men of the Reserve Police Battalion 101 unofficially dubbed this phase of the Final Solution the Judenjagd, or “Jew hunt.” George Leffler of Third Company recalled, “We were told that there were many Jews hiding in the forest. We therefore searched through the woods in a skirmish line but could find nothing, because the Jews were obviously well hidden. We combed the woods a second time. Only then could we discover individual chimney pipes sticking out of the earth. We discovered that Jews had hidden themselves in underground bunkers here. They were hauled out, with resistance in only one bunker. Some of the comrades climbed down into this bunker and hauled the Jews out. The Jews were then shot on the spot…the Jews had to lie face down on the ground and were killed by a neck shot. Who was in the firing squad I don’t remember. I think it was simply a case where the men standing nearby were ordered to shoot them. Some fifty Jews were shot, including men and women of all ages, because entire families had hidden themselves there.”

ORDINARY MEN: RESERVE POLICE BATTALION 101 AND THE FINAL SOLUTION IN POLAND

By Christopher R. Browning

Letter by Helen Baker, Venice, to Phil Baker, May 1, 1938… “Were we glad to shake the dust of Vienna from our feet…Before the election the drive against the Jews was bad, but as soon as the vote was in, they really began to put the screws on. On the last Saturday that we were there, a Nazi was stationed in front of every Jewish store to prevent Aryans from going in. We ran several experiments knowing that, as Americans, we could go wherever we chose. They stopped us, asked if we were Aryan, and then informed us that it was a Jewish store. With one exception, it was sufficient to say that we were “Auslander” [“foreigners”], but this man was downright mean and threatened to arrest me if I went in. It was too close to our departure to take any chances…Jewish restaurants were raided by Nazis, and everyone had to show his pass to prove that he was Jewish. An Aryan caught buying in a Jewish store was often made to walk the streets wearing a large placard [saying,] “Ich bin ein Deutsches Schwein und kauf’ bei Juden ein” [“I am a German swine and buy at Jewish shops”]. They even branded some on the forehead with indelible ink, with this same rhyme…Of course the suicides among the Jews and the active members of the Vaterländische Front reached appalling numbers. One doctor that we know of was called for sixty [suicides] in one day, and there were probably about two hundred daily for the first week or two.”

JEWISH RESPONSES TO PERSECUTION

By Jurgen Matthaus and Mark Roseman

Andre Lettich has provided the following description of Block 7, which was for a long time connected with the infirmary in the Birkenau men’s camp: “Even from a distance one became aware of a terrible stench from decaying and putrefying excrement. If one passed through the gate and reached the yard (this block was surrounded by a wall two meters high), there was a truly horrible sight. To the left of the gate there were poor wretches with broken limbs, cellulitis, edemas, and every conceivable deficiency disease. A bit farther, other patients who seemed somewhat less frail dragged themselves along. Lastly, at the far end of this hideous yard, corpses and living skeletons were intermingled. When we entered this courtyard in our first months in Birkenau, people who knew us stretched their imploring hands toward us from all sides and we heard heartrending screams: ‘Doctor, help us.’ This profusion of unimaginable human misery, this host of diarrheic patients and enfeebled prisoners, was a frightful sight. All were indescribably emaciated, most of them were almost completely naked, and their underwear and clothes, which had not been changed, were filthy all over. Three wooden boxes in the middle of the yard served as toilets. Those boxes, which were rarely emptied, overflowed, and thus an area within a radius of about two meters was flooded with urine. What a horrible sight it was when all those down-and-outers, the walking skeletons and ailing people, pitifully dragged themselves to those boxes, and, no longer able to stay on their feet, fell into the muck and struggled with death until it finally put an end to their pitiable situation.”

PEOPLE IN AUSCHWITZ

By Hermann Langbein

Dora [Germany] survivors recalled that the worst part of camp existence began in November 1944. New guards and officers came from Auschwitz and other evacuated camps where they were accustomed to using arbitrarily cruel methods on inmates. They quickly took out their anger and frustrations on the Dora prisoners. The prisoners remember one day when the guards hanged fifty-seven inmates: They were hanged in the tunnels with the help of an electrically controlled crane, a dozen at one time, their hands bound behind the back. A piece of wood was put in their mouth, and held fast by a wire tied at the back of the head in order to prevent shouting. All the prisoners had to attend these mass-hangings, which were allegedly a result of sabotage. Sabotage, by the Gestapo and the SS, was a very extensible word! Sometimes the use of a paper cement bag to keep warm, the use of a piece of scrap metal to make a spoon, the use of a piece of electrical wire to hold wooden shoes on the feet, or other trifling measures were considered as sabotage, and resulted many times in death by hanging or being beaten to death in the bunker.

Shortly before the war, the Germans established another major subcamp called Nordhausen…The obvious goal was slow but sure extermination. With little food and no medicine, death rates of 35 to 50 people a day were usual, and toward the end of the war 75 people a day died out of a camp of 4,000 inmates.

Ohrdruf’s medical facility could be called a hospital in name only. Most of the ill inmates lived in animal quarters. A prisoner, Dr. Bernhard Lauber, testified to the conditions: “They were accommodated in the stables. There were no beds in those stables. It was a concrete floor. The sick people lay on the bare floor, without straw, without covers and blankets; no drugs; and these ill people were given 50 percent of the food which we were given. They were so ill they couldn’t eat very well. They lay there with open wounds, they were not dressed, and they died there by the thousands.”

HITLER’S DEATH CAMPS

By Konnilyn G. Feig

Henryk Mandelbaum, a Polish Jew, worked as one of the Sonderkomandos in the new Auschwitz crematoria/gas chambers in 1944. “You can’t really think about it,” he says. “I thought I was in hell. I remember sometimes when, if I did something wrong at home, my parents would tell me don’t do it because you’ll go to hell. But when I saw many human corpses, people who were murdered through gassing and they were being burnt…it was beyond anything I could imagine and I didn’t really know what to do. If I refuse [to work there] then I’ll be gone, right? I knew they would kill me. I was young. I lost my family. They were gassed – my father, my mother, my sister and brother. So I was aware of it and I wanted to live and I fought. I struggled to live all the time.”

Henryk Mandelbaum remembers that, despite the efforts of the SS to keep an atmosphere of calm as the Jews were ushered into the gas chamber, sometimes people “started to sense something was wrong. There were too many people and some wanted to withdraw, but the SS men would hit them in the head with sticks and blood was flowing. So there was no chance of withdrawing or getting out, but by force they would be pushed into the gas chambers. When it was full they would lock the door – the doors were hermetic like refrigerators.” He recalls that behind every transport “there was an ambulance with a red cross [on it]” and, in a cynical act, “in that red cross ambulance they [the SS] had Zyklon B gas [crystals].” Once the crystals had been thrown into the gas chamber, “the gassing lasted about twenty minutes to half an hour. After the gassing, after the twenty or thirty minutes, we opened the doors. You could see how these people died – standing. Their heads were to the left or to the right, to the front, to the back. Some vomited or had hemorrhaged, and they would shit with loose bowels. Before the burning we had to cut their hair and pull out the gold teeth. And also had to look whether people kept anything in their nostrils, or valuables in their mouth – women in their vaginas.”

THE HOLOCAUST

By Laurence Rees

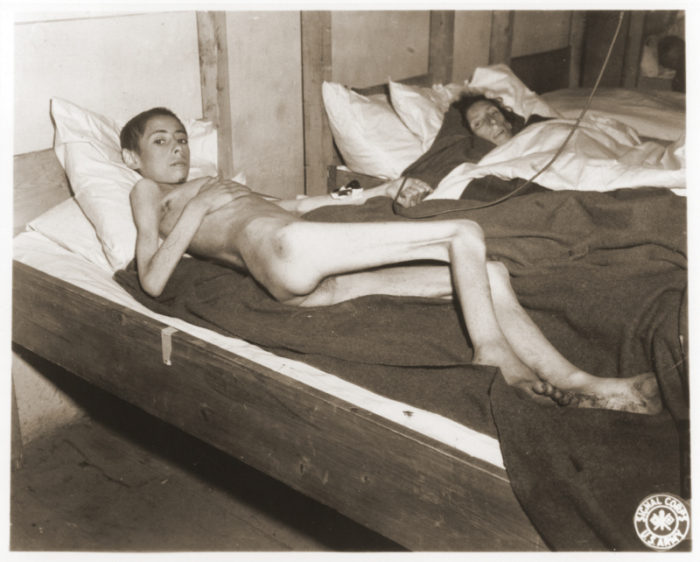

Two emaciated female Jewish survivors of a death march lie in an American military field hospital in Volary, Czechoslovakia.

“One further incident I remember was a large-scale execution by firing-squad which took place at a well on the way to Kachowka…The victims – several hundred, or even a thousand, men and women – were transported in trucks. I cannot recall whether there were any children. These people were made to lie or kneel about a hundred meters from the well in a depression which had been hollowed out by the rain and remove their outer garments there. They were lined up ten at a time at the side of the well and were then shot by a ten-man execution squad, which included myself. When they were shot the people fell forwards into the well. Sometimes they were so frightened that they jumped in alive. The firing-squad was switched a great many times. Because of the psychological pressures to which I was exposed during the shooting. I can no longer say today, try as I might, how many times I stood by the hole and how many times I was relieved from that duty.

“Obviously these shootings did not proceed in the calm manner in which one can discuss them today. The women screamed and wept and so did the men. Sometimes people tried to escape. The people whose job it was to get them to stand by the well yelled equally loudly. If the victims didn’t do as they were told there were also beatings. I particularly remember a red-haired SD man who had a length of cable on him which he used to beat the people when the action was not going as it should.”

“THE GOOD OLD DAYS”: The Holocaust as Seen by its Perpetrators and Bystanders

By Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, and Volker Riess

In 1942, a commander of the Hlinka Guard lived in her village and wanted Eva’s family’s house. So he arranged that they would be one of the first Jewish families to be deported. As a result, Eva together with her father and mother left Slovakia on 17 July, crammed into animal cargo trucks. Once on the ramp at Auschwitz her father was selected to join one line and Eva and her mother another. “From that moment I heard nothing about my father,” she says. “When I saw him for the last time he looked worried, sad and hopeless.”

Her father was taken away and murdered in the gas chamber, while Eva and her mother were assigned to a construction commando. The work was physically demanding and the prisoners received little food or water. As a result, Eva’s mother became sick: “She had a fever and a dark film on her upper teeth – which was an unmistakable sign of deadly typhoid fever. Of course, I did not know this at the time. She told me that she needed to go to the hospital [in the camp]. I cried and begged her not to go there at least for one more day. No one ever came back from there.” By now Eva knew that “people were taken straight to the gas chambers” from the hospital. When Eva came back from work the following day she learnt that her mother had, despite her pleas, been admitted to the hospital. Three days later someone who worked at the hospital told Eva that her mother “had gone.” Shortly afterwards Eva was assigned to the “corpse commando” and collected bodies from all over the camp. Among the pile of human remains, Eva found a pair of glasses. “I knew they were my mother’s – the left glass was broken after my mom had been slapped by a German Kapo.” Holding the glasses, Eva cried, and saw “all of her [mother’s] pain, sickness and misery in front of my eyes.” She kept “the glasses as the last memory of my mother until stomach typhoid fever infected me. Then they had to burn the pillow I used to hide them in. That was the last memory of my mother.”

THE HOLOCAUST: A NEW HISTORY

By Laurence Rees

“My wife has a story to tell that would take four tape recorders to hear. She’s from Poland, but she came to Italy as a baby and lived eighteen years in Italy before she left. She was hidden in a convent by the nuns. She worked for the partisans. One day a German soldier caught her and wanted to rape her. When she said no, he took out a gun and said, “You let your pants down or I’ll shoot you.” So she said, “Go ahead and shoot.” And he did, he did shoot her. They had to rush her to the hospital. She was afraid to be discovered that she was Jewish. After the operation she ran away from there, from the hospital. She went to the convent and the nuns hid her until the end of the war.

WHAT WE KNEW

By Eric A. Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband

Emma Becker was a ‘Jew’ in a situation that might be supposed to have been unusually propitious for her to have received decent treatment from her fellow Germans. Married to a Catholic, she had herself converted to her husband’s faith, thus renouncing her Jewish identity and severing formal ties to Judaism. Nevertheless, in 1940, her neighbors made it clear that they did not wish to live next to her, she evidently being, in their racially oriented minds, still a Jew. The only person who visited her was her own priest. For his kindness, for carrying out his religious duties, he himself was abused by her neighbors. She tells of other open expressions of hatred directed at her, and her complete ostracism from the ‘Christian’ community, to the point where she became a leprous outcast in her own church. Forced by others to retire from the church choir, for they did not want to sing praise to God alongside this ‘Jew,’ her ‘coreligionists’ refused to kneel beside her or take communion with her. Even priests, these men of God, who ostensibly believed in the power of Baptism, shunned her in church.

HITLER’S WILLING EXECUTIONERS

By Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

“One of my sisters survived the war in Berlin because she was hidden by a German family through to the end of the war. She was working for Siemens, a big electrical company. This factory was in a suburb of Berlin. She worked there like everybody else and then the word got around at the train station. They said, ‘You better be careful. They’re looking to arrest Jews.’ Finally they arrested them. They put them in a truck, and of course she knew what was going to happen. Everything was dark. Because they were driving through the woods and the road was bumpy, they had to go a little slow. So she took her chances and jumped off the truck and ran into the woods. Of course they saw that she had jumped and they couldn’t put on the lights so they shot her. They shot at random. Of course she was hit. They shot her in the side and she fell down in the woods. It had to be 1940 or 1941, I cannot pinpoint it. She probably passed out. And then, in the morning, a woman found her and took her home. This woman kept her hidden throughout the war.”

WHAT WE KNEW

By Eric A. Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband

Male Jews were arrested during Kristallnacht and forced to march through the town streets under SS guard to watch the desecration of a synagogue, then sent to a concentration camp.

“There was a young couple among the hundred Jews in the hiding place. The woman was a pretty, blond[AS1] -haired lady named Malka. They had a baby that was only a few weeks old. The baby’s grandmother was the woman who let my daughter and me stay in her apartment our first night in the ghetto. During the first night in hiding the baby cried often. Every time the baby cried the other people would tell the parents to keep the baby quiet, but the parents could not keep it quiet for long. The more the baby cried the angrier the other people grew and the more frantic the parents became. We knew that the SS would be prowling the streets and buildings looking for the hiding places. We all had to walk slowly and talk only in whispers. The baby’s crying put all of us in danger of being found. In the morning the noise outside got louder. The SS had come back into the ghetto. This time they had tanks, and the shooting started once again. The noise started the baby crying and the parents just could not stop it. A group of men told the young couple that they had to either leave the hiding place, give them the baby, or put it to sleep themselves. They couldn’t leave the hiding place. We were all sure that going out into the ghetto meant certain death, either from being shot on the street or from being sent to Treblinka. They also couldn’t kill the baby themselves. The couple talked quietly together for a while. Then the husband took the baby from his wife and gave it to one of the other men. The husband sat back down next to his wife, and they started to cry. The men took the baby to the other side of the room. The group of men stood around the baby so the parents could not see what was happening. They laid the baby on a table. One of the men held a pillow over the baby’s face. There was no sound in the room except the muffled crying of the baby’s parents. In a few minutes it was over, and the baby’s body was wrapped in a white tablecloth. By the next morning the baby’s body was gone. I don’t know what was done with it, and nobody talked about it again.”

THE BLEEDING SKY: MY MOTHER’S JOURNEY THROUGH THE FIRE

By Louis Brandsdorfer

Aunt Celia crawls into the dusty hole and the two sisters hold each other in a silent clasp. They have not seen each other for three years. And now, a reunion in the scorching hole, in Auschwitz. Still sobbing, Aunt Celia reaches into her bosom and takes out a lump of black substance tied on a string around her neck. She unties it and hands it to mommy. “Hear. Eat it.” “What’s this?” “It’s bread. My bread. My bread ration. Eat it. It’s yours. I want you to have it. You must be very hungry.” “This is bread? It looks like a cake of mud. How can you eat this?” “Eat it. You won’t get anything until the evening Zahlappell.” Mommy takes a bite and tears spring into her eyes. “I can’t eat this.” “You must. There’s nothing else.” She takes another bite, swallows it, and promptly throws up. Her tears flow on dusty cheeks. “I can’t. I’d rather starve.” Aunt Celia cries, too. She bends down to wipe away the tears with the edge of her prison garb. “Laurie, if you don’t want it you will not live. You must.” I snatch the bread from mommy’s hand and begin to eat it. The dry, mud-like lump turns into wet sand particles in my mouth. The others have eaten it. I swallow. The first food in Auschwitz. To survive.

I HAVE LIVED A THOUSAND YEARS

By Livia Bitton-Jackson

A non-Jewish woman recorded in her diary. It was October 1942 in Stuttgart: “I rode on a tram. It was overcrowded. An old lady got on. Her feet were so swollen that they bulged out of the top of her shoes. She wore the Star of David on her dress. I stood up so that the old lady could sit. By this I provoked – how else could it be? – the so well-practiced ‘popular fury.’ Someone yelled ‘Get out!’ Soon a whole chorus yelled ‘Get out!’ Amidst the din of the voices, I heard the outraged words: ‘Jew-slave! Person without dignity!’ The tram stopped between stations. The conductor ordered: ‘Both of you get out!’ Such was the spontaneously expressed hatred for a forlorn member of a people who were then being slaughtered.’”

HITLER’S WILLING EXECUTIONERS

By Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

Lomazy [Poland] was a town of less than 3,000, more than half of whom were at this time Jews. Of the 1,600 to 1,700 Jews whom the Germans found in Lomazy, most were not local Polish Jews, but from elsewhere, including from Germany, some even from Hamburg. The Germans had deported these Jews over the previous months to Lomazy as a first step in the two-stage process of killing them. Although a walled-in ghetto did not constrain them, the Jews were concentrated in their own section of the city. It took the men of Second Company about two hours to round up their victims and to bring them to the designated assembly point, the athletic area neighboring the town’s school. The roundup proceeded without pity. The Germans, as Gnade had instructed in the pre-operation meeting, killed those on the spot who on their own could not make it to the assembly point. The dedication of the men to their task is summarized in the court judgment:

“The scouring of the houses carried out with extraordinary thoroughness. The available forces were divided into search parties of 2 to 3 policemen. The witness H. has reported that it was one of their tasks to search also the cellars and attics of the houses. The Jews were no longer unsuspecting. They had learned of what was happening to the members of their race in the whole of Generalgouvernement. They therefore attempted to hide and thus to escape annihilation. Everywhere in the Jewish quarter there was shooting. The witness H. counted in his sector alone, in a bloc of houses, about 15 Jews shot to death. After 2 hours or so the easily surveyed Jewish quarter was cleared.”

The Germans shot the old, the infirm, and the young, on the streets, in their homes, in their beds.

HITLER’S WILLING EXECUTIONERS

By Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

The march to Bergen-Belsen, a distance of over 250 miles as the crow flies, lasted one month. The prisoners covered almost the entire distance on foot, sleeping mainly in unheated barns. Along the way a large though indeterminate number of prisoners died or were shot by the Germans… “Almost all of us had no decent footwear; a great number had to walk barefoot or had their feet wrapped in rags. During the time of the march, the ground was throughout covered with snow.” Some trudged along barefoot. The march to Helmbrechts covered about three hundred miles. It was in the middle of winter. Of the 1,000 to 1,100 who set out on this march, 621 arrived in Helmbrechts almost five weeks later. The Germans had deposited around 230, including the sick, at other camps, and a few had escaped. Between 150 and 250 women did not survive the journey, in part because of the brutal conditions: “After several days without food or drink – we spent the nights outdoors in the snow, the conditions were extremely bad – many died from exhaustion. Every morning when we got up, many remained lying lifeless on the ground.” Yet most of those who perished appear to have been shot by the Germans, often for having lagged behind. The Germans shot fifty women during one massacre. In addition to the killings, this death march had the usual assortment of German violence and torment: brutal beatings, inadequate food, appalling clothing and shelter, and general terror.

HITLER’S WILLING EXECUTIONERS

By Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

Studio portrait of Anita Randerath, a young Jewish girl, who was murdered shortly after this photo was taken.

Studio portrait of Anita Randerath, a young Jewish girl, who was murdered shortly after this photo was taken.

On November 12, 1941, Himmler ordered Friedrich Jeckeln, the HSSPF Ostland, to murder the approximately thirty thousand Jews of the Riga [Latvia] ghetto…In the early morning hours the trek from the ghetto to the nearby Rumbula forest began. Some seventeen hundred guards were ready, including a thousand Latvian auxiliaries. In the meantime several hundred Soviet prisoners had dug six huge pits in the sandy terrain of Rumbula. As group after group of the ghetto inhabitants reached the forest, a tightening gauntlet of guards drove them toward the pits. Shortly before approaching the execution site, the Jews were forced to dispose of their suitcases and bags, take off their coats, and, finally, remove their clothes. Then the naked victims descended into the pit over an earthen ramp, lay face down on the ground or on the bodies of the dying and the dead were shot in the back of the head with a single bullet from a distance of about two meters. Jeckeln stood on the edge of the pits surrounded by a throng of SD, police and civilian guests. Twelve marksmen working in shifts shot the Jews throughout the entire day. The killing stopped sometime between 5 and 7 p.m.; by then, about fifteen thousand had been murdered. A week later, on December 7 and 8, the Germans murdered the remaining half of the ghetto population.

NAZI GERMANY AND THE JEWS 1933-1945

By Saul Friedlander

The final entry in Egon Redlich’s diary, dated October 6, 1944, was part of the ‘Diary of Dan’ [the name of his newborn son], in which he commented on the events by addressing his infant child: “Tomorrow we travel son. We will travel on a transport like thousands before us. As usual, we did not register for this transport. They put us in without reason. But never mind, my son, it is nothing. All of our family already left in the last weeks. Your uncle went, your aunt, and also your beloved grandmother…Tomorrow, we go too, my son. Hopefully, the time of our redemption is near.” Redlich and his infant son were murdered on arrival.

NAZI GERMANY AND THE JEWS 1933-1945

By Saul Friedlander

“One day I was walking down the street with a friend and two German officers from the Nazis stopped their car and said, ‘I take you with me, you come here.’ Like a kid with a big mouth, I then said to them in German, ‘You can’t take me. I’m too young to go.’ He gave me right away a slap on the face, a big hard one, and said, “You come with me.” And then they took me and the girl who had walked with me into the school. Later on they rounded up a lot of Jewish girls from that town, I think about forty, and we were sent to a transport camp…But sometime in September or October 1942, my brother, my parents, my grandparents, and my cousins were all taken to Auschwitz and nobody ever saw them again. Then they came at the same time to my camp; maybe it was a few days later [and we were sent to Auschwitz].”

WHAT WE KNEW

By Eric A. Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband

“A goods train traveled directly into the camp of Belzec, the freight cars were opened and Jews whom I believe were from the area of Romania or Hungary were unloaded. The cars were crammed fairly full. There were men, women and children of every age. They were ordered to get into line and then had to proceed to an assembly area and take off their shoes…After the Jews had removed their shoes they were separated by sex. The women went together with the children into a hut. There their hair was shorn and then they had to get undressed…The men went into another hut, where they received the same treatment. I saw what happened in the women’s hut with my own eyes. After they had undressed, the whole procedure went fairly quickly. They ran naked from the hut through a hedge into the actual extermination center…Inside the building, the Jews had to enter chambers into which was channeled the exhaust of a [100?]-HP engine, located in the same building. In it there were six such extermination chambers. They were windowless, had electric lights and two doors. One door led outside so that the bodies could be removed…After about twelve minutes it had become silent in the chambers. Jewish personnel then opened the doors leading outside and pulled the bodies out of the chambers with long hooks. To do this they had to put these hooks in the mouths of the bodies. In front of the building they were once again examined and the bodily orifices were searched for valuables. Gold teeth were ripped out and collected in tins.

“THE GOOD OLD DAYS”

By Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, and Volker Riess

Late that night, after hours on our feet, we approached a creek, with a footbridge across it. There was noise, a disruption of some kind ahead of us. I couldn’t tell what was happening. As I got closer, I saw a handful of German soldiers, not our guards, but other, younger ones, with sticks and clubs in their hands. They had been drinking. As people were forced to cross that bridge, the soldiers pelted and struck them with fence posts, nails still hanging from them, hit them on heads and shoulders, shouting, “Das is für mein Vater, das is für meine Mutter, und das is für mein Vaterland!” They were drunk, crazy, and I was coming right up to them and didn’t know what to do, so I threw my backpack at the soldier who was about to strike me, threw it at his feet. He stumbled backwards and I ran past the rain of sticks and clubs and somehow passed the soldiers untouched. The next morning, just before dawn, we stopped marching at last and were told to go sleep in a nearby field for the day. As the sun rose, we could see how many of us were injured the night before. Bleeding heads and arms, torn clothing and hidden wounds everywhere. People tore off part of their clothing to clean and bandage themselves. Some of the women were crying. Dozens were hurt.

I CARRIED THEM WITH ME

By Sara Lumer

Three elderly Jews walk arm-in-arm through the streets of Krakow during the final liquidation action of the ghetto. Old people were murdered first.

Once strong and able to pass for an older boy, I had become frail and my body began to break down. My teeth and gums ached from lack of solid food. I had a great urge to bite down on something with some substance. In desperation, I tore off some of the sole of an old shoe and chewed on it as if it were a piece of the finest filet. It felt good to use my jaws. Jacob, who was then just five years old, noticed me chewing and thought it could only be food. So, he tugged on my arm and begged me to open my mouth. He called me names and cried for me to share with him. I gave him the piece of old leather and before he could walk across the room he had swallowed it. His stomach was so empty that he could not control himself. He started to cry and I took him in my arms to comfort him.

OUTCRY: HOLOCAUST MEMOIRS

By Manny Steinberg

One of the many affecting stories is that of a patient named Frau Rosenberg. She and her husband, both Jewish, had gone underground to avoid deportation. One day, the wife went out to search for food, was hit by a bus, and suffered a severe concussion. She was taken to a German hospital where her false identity was unmasked and it was discovered that she was a Jew. She immediately transferred to the [Jewish] hospital, where the doctors and nurses made her as comfortable as possible. One day Eichmann and Wohrn came into the ward where she was lying in bed and began to interrogate her about her husband’s location. Frau Rosenberg said that she had no idea, pretending the injury she had sustained to her head made her lose her memory. At Eichmann’s command, Wohrn hit her in the face. Eichmann then told her that they would return in a week and give her one more chance to tell them the truth. A week later the same scene was replayed, but Frau Rosenberg remained adamant in claiming that she had lost her memory. Eichmann again ordered Wohrn to beat her in the face and told the poor woman that she had one more week, that the next time would be her last opportunity to save herself. One morning during the intervening week, Frau Rosenberg’s dead body was discovered in her bed. A male nurse named Mayer had taken pity on her and supplied the pill that she used to kill herself. Unaware of what had happened to his wife, Herr Rosenberg managed to remain in hiding and survived the war. After the liberation, he turned up one day at the hospital looking for his wife, and someone on the staff had the task of telling him how she had died.

REFUGE IN HELL

By Daniel B. Silver

On the afternoon of 25 April 1938, after six weeks of Nazi domination in Austria, I was on the way home. Near our apartment a Jewish gymnasium was located in the cellar of Liechtensteinstrasse 20. As I got near this building, I was stopped by Nazis, who made a chain and carried armbands with swastikas. One shouted at me, “Are you a Jew?” When I said yes, he pushed me to the building, where the gymnasium was, and ordered me to go downstairs. In this anteroom of the gymnasium I saw about 20 to 25 Jews, whom the Nazis had seized before me and had pushed them together into a corner. A Nazi pushed me there. The large gymnasium and also this anteroom were, by your leave, perfectly covered with shit. The floor and also the walls were completely covered with excrement. It stank atrociously. By my estimation, a whole regiment of SA or SS or some other Nazis must have relieved themselves there. And then one shouted: “Now get going! To work!” Some Jews actually tried to scrape the excrement together by hand and throw it into the toilet bowl. But that was impossible. At best one could only smear the excrement. It was not possible to clean the anteroom and the gym this way. The Nazis laughed and jeered at us, but eventually brought a scoop, a broom, a bucket, and a couple of rags, and we turned the water faucet on. But one would have needed a fire hose to clean up. I took a rag in my hand, had a frantic fear of being killed by the Nazis in this cellar, and tried to crawl behind the other Jews and throw the excrement into the toilet. The whole thing lasted 15 or 20 minutes, during which we tried to follow the orders of the Nazis.

SOURCES OF THE HOLOCAUST

By Steve Hochstadt

In the days after Kristallnacht, Herbert Friedlander gathered his money and passport and boarded the train for Hamburg, the location of many foreign consulates and embassies. “The Jewish people,” his daughter, Inge, recalls, “always talked to each other. There is something here. A possibility here. So he went to the Uruguayan consulate and he bought visas. Ok, he bought visas. That’s what you did at the time.” As soon as he returned to Berlin, he purchase ship tickets. The Friedlanders now had their lifeline: visas and a passage to Montevideo. Yet even with these precious documents, they faced the dangers of everyday life in Nazi Germany. Answering a knock on the door one evening, Herbert’s wife, Paula, was shocked to face members of the Gestapo. They had come for Herbert, who fortunately was not in. Aiming to prevent future visits, Paula pointed to the packed suitcases and explained they were leaving Germany. For safety, Herbert spent the next few nights in the home of non-Jewish friends.

Amid the hurried packing, selling what they could, saying their good-byes, and avoiding the Gestapo, the family never stopped to imagine their new life in far-off South America. “It was just a way out,” remarks Inge Friedlander. “There was no thinking how it would be. It was out, out of Germany. That was all that mattered.” Once on the ship and bound for Uruguay, the family finally had a chance, if not to relax a bit, at least to shake off some nervousness and fear. For the teenaged Inge, the ship passage was a “good time.” There were people of her age, particularly young, attractive men, a whole mix of people with whom she could socialize. But as Herbert Friedlander wrote in his letter to Luzie, their plans to settle in Uruguay went terribly wrong.

Dear all,

You might have heard of our fate; we are in great despair; we are unable to land in Montevideo; the visas have been denied. We then had to go to Buenos Aires, where we were held in custody and could not leave the ship for 10 days, and later had to go back. They strung us along with promises from day to day. There were negotiations with Chile and Bolivia, but nothing worked out. Now we are facing the worst: going back.

EXIT BERLIN

By Charlotte R Bonnelli

Among the Jews rounded up on August 26 in the unoccupied zone, 550 were from Lyon who were taken to an empty factory in the suburb of Venissieux while awaiting transfer to Drancy [France]. Families sat huddled in the dark, trying to grasp what was happening. Garel and Glasberg decided to persuade families to give up their children. This was a very strange job of salesmanship. They had to talk to people they didn’t know, who often spoke little or no French, and convince them to leave their children behind in the hands of complete strangers. “You can imagine what it was like,” recalled Garel, “going up to people and saying, ‘Give us your children.’ You couldn’t tell them, ‘You are doomed, let the children survive.’ We had to say as little as possible. And in the dark it was hard to find the families with children. So we decided to give orders rather than to plead. We said, ‘We came for your children.’ Sometimes we used physical force to pull them away.” Sometimes parents agreed, putting on a cheerful face for the sake of their children and promising that they would be back to get them soon.

AN UNCERTAIN HOUR

By Ted Morgan

Corpses lie in an open area in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

“It turned out that the walls [synagogue in Kovel, Ukraine] were covered with writing in pencil. There was not a single empty spot on the wall. These were the last words of the doomed, their farewell to this world. The Nazis had driven people in here, and then after robbing them of everything down to their last stitch of clothing, had led them out naked to be shot somewhere outside of Kovel…Here are some of their words: ‘Leyb Sosna! Know that they killed all of us. Now I’m going with my wife and children out to die. Be well. Your brother Avrum. August 20.’ ‘Dear sister! Maybe you managed to save yourself, but if you’re ever in the synagogue, read these words. I’m in the synagogue and waiting for death. Be happy, and survive this bloody war. Remember your sister. Polya Friedman.’ ‘September 21 Bar Khana, Bar Zeidik, Avrum Segal, Petl Segal, Falik Bar – they died eight weeks ago along with their brother-in-law David Segal.’ ‘Ida Soyfer, Zelig Friedman, Friedman with wife and children. Tserun Leyzer with his daughters and Sroul Katz died at the hands of the German murderers. Avenge them!’ ‘Gitl Zafran from 6 Street, Rina Zafran had her throat cut on Thursday.’ ‘Borya Rosenfeld and wife Lama died August 19, 1942.’ ‘August 20, 1942, Zelik, Tama, Jela Kozen perished. Avenge us!’ Liza Rayzen, wife of Leybish Rayzen. The dream of every mother, to see her only daughter Beba, living in Dubno, did not come true. With great pain she goes to her grave.’”

THE UNKNOWN BLACK BOOK

By Joshua Rubenstein and Ilya Altman

Jakob and Miriam had lived with nine other people in one room in the [Skala] ghetto. The constant fear of a raid, the starvation rations, the continuous harassment for contributions by the Judenrat, and the spreading contagion of typhus and typhoid must have brought them to despair. They had no money for bribes with which to buy their freedom, no chance of escaping to the forest, no Jan to look after them. And they were in their sixties. When the alarm reached them, they rushed to their hiding place in the cellar. Grandmother Miriam and some other people managed to get in, but by fluke Jakob was caught outside. As the Ukrainians dragged him off, he broke away. Running to a German officer, he fell to his knees and offered to tell where Jews were hiding in exchange for his life. A red scarf was tied around his neck and he led the Germans to the hiding place, calling, “Miriam, it’s safe. You can come out.” As a trapdoor opened from inside and people crawled out, the Germans kicked and beat them, with Jakob looking on. They were taken out of town with the rest of the Jews, forced to dig a pit, ordered to undress, lined up, and row after row they were shot and their bodies tumbled into the pit. In a short time the pit was overflowing with corpses and blood, and a deeper one had to be dug. As she went to her death, Miriam knew that her husband had betrayed the bunker to the Germans. She saw him standing there by the pit among the Germans and the Ukrainian militia, who forced him to watch the shootings… the German officer came up to him, gun in hand, saying, “This is how we repay traitors,” and shot him in the mouth.

LOVE IN A WORLD OF SORROW

By Fanya Gottesfeld Heller

Early one morning, not fully awake in the barn’s gloom, I heard Rex barking, which he always did when strangers were approaching. I peered through a chink in the barn wall: Gestapo men were swarming out of cars and motorcycles. Ukrainian militiamen were gesturing with their rifles. Rex’s barking saved us, giving us the few precious seconds we needed to disappear into the hiding place. My father had barely pulled in his legs after mine before I, lying on the floor, saw boots passing back and forth in front of the hole in the barn wall… “Where are those damned Jews? Damn that Benjamin Gottesfeld with his sow of a wife and two lousy children!” a voice bellowed in German a few inches beyond the wall. He shouted orders to the Ukrainians to search every corner of the barn… My mother put her hand over Arthur’s mouth. It wasn’t necessary. We were too stunned to move or cry out. My mother’s teeth chattered for a few seconds until she managed to clamp her jaws together. My father dug some old throat lozenges out of his pocket and popped one in each of our mouths… The Germans ordered the Ukrainians to dig holes in every part of the barn in the belief that we had a hiding place under the ground or had dug a tunnel that led under the river to the forest. Tears and saliva flowed from me. All my sphincters opened and left nothing inside. We soiled ourselves and each other over and over again…We crawled out of the coop, filthy and stinking…and we all cried, sometimes falling against each other.

LOVE IN A WORLD OF SORROW

By Fanya Gottesfeld Heller

Odessa doctors who perished

Professors

1) Ya. S. Rabinovich Neuropathologist

2) M. Fayngold Dermatologist

3) L. P. Blank Neuropathologist

4) B. C. Rubinshteyn Histologist

Doctors

5) E. M. Bikhman Stomach Ailments

6) A. F. Goldenberg Therapist

7) N. A. Goldenberg (his daughter) Neuropathologist

8) Petrushkin Pediatrician

9) Filler Venereologist

10) Chatskin Public Health Doctor

11) Brodsky Public Health Doctor

12) Brodskaya Dentist

13) Varshavskaya Therapist

14) Varshavskaya Dentist

15) Zinger Therapist

16) Zusman Therapist

17) Gurfinkel Urologist

18) Orlyuk Dentist (woman-doctor)

19) Shkolnik Dentist (woman-doctor)

20) Kamenetsky Therapist

21) Kamenetskaya Laryngologist

22) M. L. Chernyavker Pediatrician

23) E. L. Chernyavker Gynecologist

24) E. I. Revich Pediatrician

25) S. I. Revich Pediatrician

26) Khuvo Therapist

27) G. M. Rubinshteyn Neuropathologist

28) Svoren Malaria Specialist

29) Shapiro Venerologist

30) Chudnovsky Gynecologist

31) Zaynfeld Gynecologist

32) Guz Lecturer-Therapist

33) Kirbis Neuropathologist

34) Pasternak Therapist

35) Gorovitz Surgeon-Urologist

36) Bronfman Therapist

37) Goldberg Venerologist

38) P. M. Furman Epidemiologist

39) Galbershtadt Stomach Ailments

40) Fishberg Therapist

41) Frak Pediatrician

42) Teplitsky Therapist

43) Velderman Therapist

44) Birbraf Venerologist

45) Fayngersh Therapist

46) Levi Dentist (woman)

47) Levi Dentist (man)

48) Bronshteyn Dentist

49) Gaukhman Dentist

50) Gauzenberg Dentist

51) Frenkel Doctor-Biochemist

52) P. I. Polyavka Doctor-Laboratory Researcher

53) N. M. Moshkovich Doctor-Laboratory Researcher

54) Zhvier Laboratory Researcher

55) Burman Doctor-Laboratory Researcher

56) Mikman Laboratory Researcher

57) Gorn Pharmacist

58) Elzon Pharmacist

59) A. A. Zaydelbern Public Health Director

60) Kan Tuberculosis Specialist

61) a. m. Zamels Venerologist

With their families, including twenty-four women doctors.

THE UNKNOWN BLACK BOOK

By Joshua Rubenstein and Ilya Altman

We bury women [at Neustadt camp in April 1945, days before the war ends] all day and get in after roll call, after the bread has been handed out. There is nothing left. No food for those of us who have worked all day… At the pile of coal I check the vicinity, grab two potatoes, and thrust them under the coal in the bucket. Head forward, eyes down, I walk slowly across the compound. Out of the shadows by the blocks I hear the camp elder’s voice, “Let me see you empty that bucket on the ground.” I freeze and turn slowly around. “Well?” I dump the contents onto the ground. The potatoes could be covered by enough black dust to be masked amidst the odd-shaped lumps of coal that she won’t see… She hits me in the left eye before I can even think to duck. “You stole potatoes!” She throws me on the ground, kicking me, stomping on me with her boots, trying to tear the flesh from my bones with her fingernails. I cannot see anything but the blazing hatred in her face; it is the face of Death itself. She loses her grasp on me for a second. I scramble away, fleeing across camp. “Thief! Thief! Scheiss-Jude! Get back here you filthy dog!” Her harpy’s voice follows my tracks like a bloodhound hot on the trail. I vanish behind the blocks, dodging searchlights and the madwoman’s voice. Under the cover of darkness I slip into one of the other blocks. “I stole a potato and she’s going to kill me for sure,” I whisper into the dark.

“Come here.” An anonymous voice calls out. Quickly, I crawl in between two bodies, and hide under their blanket. Outside the wardress screeches, “Come out you miserable mist biene! Come out here! You can’t hide forever. I’m going to get you!” It seems a lifetime until she quiets down. I wait for a little bit longer, just to make sure she’s not hiding somewhere, and then slip out of the bunk I’ve hidden in. “Thank you for saving my life,” I whisper to the girls whose faces I do not know, then creep back across camp, so the wardress won’t know which block has hidden me. Blinded in my left eye, I thread my way through the shadows and along walls until I reach our block.

RENA’S PROMISE

By Rena Kornreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam

Members of Police Battalion 101 celebrate Christmas in their barracks. They shot and brutally murdered thousands of Jews, including children.

Two SS men conducted the selection [who would be gassed], both with their backs to the rear wall. They stood on opposite sides of the so-called chimney, which divided the room. In front of each was a line of naked, or almost naked, women, waiting to be judged. The selector in whose line I stood had a round, wicked mask of a face and was so tall that I had to crane my neck to look up at him. I told him my age, and he turned me down with a shake of his head, simply like that. Next to him, the woman clerk, a prisoner, too, was not to write down my number. He condemned me as if I had stolen my life and had no right to keep it…My mother felt I could sneak by and take another turn. And this time, please don’t’ be a fool and tell them your real age of twelve. I got angry and was half desperate. “I don’t look older,” I remonstrated… “You are a coward,” she said half desperately, half contemptuously, and added, “I wasn’t ever a coward.” So what could I do but go in a second time, but with the proviso that I would try thirteen, never fifteen… The space between the barracks I was to invade in order to reach the back door was guarded by a cordon of men. My mother and I watched them carefully for a minute or so. “Now!” we realized, and I sneak by as the two men in charge happened to call out to each other. I bent over a little to appear smaller, or to make use of the shadow of the wall, turned the corner, and entered through the door, unobserved… I went unobtrusively to the front door, took off my clothes once more, and quietly went to the end of the line. I breathed a sigh of relief to have managed so far so well, and was happy to have been smarter than the rules. I had proved to my mother that I wasn’t chicken. But I was the smallest, and obviously the youngest, female around, undeveloped, undernourished, and nowhere near puberty. I have read a lot about the selections since that time, and all reports insist that the first decision was always the final one, that no prisoner who had been sent to one side, and thus condemned to death, ever made it to the other side. Alright, I am the proverbial exception…The line moved towards an SS man who, unlike the first one, was in a good mood. Judging from photos, he may have been the infamous Dr. Mengele, but as I said, it doesn’t matter. His clerk was perhaps nineteen or twenty. When she saw me, she left her post, and almost within the hearing of her boss, she asked me quickly and quietly and with an unforgettable smile of her irregular teeth: “How old are you?” “Thirteen,” I said, as planned. Fixing me intently, she whispered, “Tell him you are fifteen.” Two minutes later it was my turn, and I cast a sidelong look at the other line, afraid that the other SS man might look up and recognize me as someone whom he had already rejected. He didn’t. (Very likely he couldn’t tell us apart any more than I had reason to distinguish among the specimens of his kind.) When asked for my age I gave the decisive answer, which I had scorned when my mother suggested it but accepted from the stranger. “I am fifteen.” “She seems small,” the master over life and death remarked. He sounded almost friendly, as if he was evaluating cows and calves. “But she is strong,” the woman said, “look at the muscles in her legs. She can work.” She didn’t know me, so why did she do it? He agreed – why not? She made a note of my number, and I had won an extension on life.

STILL ALIVE

By Ruth Kluger

“We all stayed there [hiding in a sewer] for a few days. Some people couldn’t take the stench and the darkness, so they left, but ten of us remained in that sewer – for fourteen months! During that time we never went outside or saw daylight. We lived with webs and moss hanging on the wall. The river not only smelled terrible, but also it was full of diseases. We got dysentery, and I remember Pavel and I were sick with unrelenting diarrhea. There was only enough clean water for us to have half a cup a day. My parents didn’t even drink theirs; they gave it to Pavel and me so that we wouldn’t die from dehydration…

“Then there was a heavy rainstorm, and the sewer swelled so that the water was almost up to the ceiling, which was less than five feet high. My parents, who were constantly bent, had to hold us children up high so that we could breathe. We were frequently soaking wet. The rats were all over us – each one was about a foot long. But we weren’t afraid of them; we played with them. We fed them, they grew even bigger from eating our bread. But they always wanted more, and my father had to stay awake at night to keep them from eating it all.”

THE HIDDEN CHILDREN

By Jane Marks

As we sat down to our meal one night early that spring, we heard an abrupt knock on our door. Then came the familiar “Open up!” that we had heard several times in our building. Two more forceful knocks followed. Mother went to the door, resigned to opening it and facing the Nazis. She looked into the cold eyes of two Gestapo agents, who greeted her with the familiar “Heil Hitler!” Mother didn’t respond, but she opened the door to let them in. my aunts and I sat frozen in our chairs as the two Gestapo men marched in, proudly wearing their Nazi uniforms and swastikas. “We are here to arrest Kate Suessman. Which one of you is she?” “It is I,” Aunt Kate replied. “What have I done?” Relief and horror were written on Mother’s face. At least they didn’t want me or her other two sisters, who were in poor health. “Does it matter what the reason is for a Jew’s arrest?” the self-appointed Gestapo spokesman answered. “Jews need only exist; that is reason enough for their arrest. You have five minutes to fill one bag with things and that is all. Hurry now.”…

“I insist that you tell me why she’s being arrested,” Mother said, “and why are you taking her instead of me?” “I only pick you people up,” the Gestapo agent replied coldly, his arms folded impatiently in front of him. “I just follow my orders. I don’t ask questions and neither should you. Your neighbors, the Ephraim’s, are also being taken today. You can check at the police station tomorrow; they might tell you where they have been sent.” Aunt Kate filled a brown bag with some small essentials and then bundled up to leave for her unknown destination. All the rest of us choked back our tears, although Aunt Kate was being very brave as she faced the ordeal. Lining up at the door, we each gave her a hug before the Gestapo agents pushed her out into the hall. Across from us, we saw the whole Ephraim family silently gathering a few belongings. It made no sense to us that some Jews were being picked up while others weren’t. Some family members were taken while others were left behind, even though for all Jews the everyday life anywhere in Germany was like living in a prison. But the selection for arrests seemed to be done at random, perhaps on the whim of the Gestapo officer who was in charge for the day.

Aunt Kate was led down the stairs and put in to a Gestapo wagon while Aunt Friede, Aunt Elsbeth, Mother and I gazed sadly out our front window at the agony below. Normally an extremely nervous lady, Aunt Kate was unbelievable brave. We stared blankly as the wagon drove off down the street and grew small in the distance…

One day by one of the apartments in our Jewish tenement were emptying as the arrests increased. In June, we heard the dreaded knock again. This time they came for Aunt Friede, who was seventy-three years old. We tried very hard to swallow our tears again, for we knew it would only upset Aunt Friede more to see us crying over her. Again, no explanation was given and no destination revealed. A great part of the terrifying fear related to the arrests was the unknown factor of the prisoner’s destination. Was it jail or a concentration camp? Was it a work camp or a gas chamber or a firing squad? … We sat quietly as Aunt Fried gathered a handful of belongings. Mother smiled bravely at me, trying to comfort me from across the room. “She is a sick, old lady,” Mother protested to the Gestapo agents. “It would be better for you to take me. I am strong and healthy.” “My orders are to pick up Friede Markuse,” one of the men replied…

We kissed Aunt Friede and watched the old, white-haired lady hobble down the street on her arthritic feet. Balancing herself with her cane, she was helped into the police wagon – a pathetic and haunting sight that burned itself into my memory. Two weeks later the ugly scene repeated itself as Aunt Elsbeth was picked up. The Gestapo virtually pushed our door down and then screamed at us. “Which one of you is Elsbeth Suessman?” Aunt Elsbeth’s feeble heart nearly stopped beating as she was ordered to gather her things. Then the Gestapo agents labeled some of her few remaining possessions. “These are now the property of the state,” they said. “We will pick them up later. You are not to touch them, do you understand?” “This woman has a bad heart,” Mother said as they waited for Aunt Elsbeth. “She is under a doctor’s care and must receive constant medical attention. Will she get that where you are taking her?” “Shut up!” came the reply. Impatiently they paced the apartment as Aunt Elsbeth gathered her things. “That’s enough!” one said. “Come with us now!” Aunt Elsbeth was white with fear, but resistance would do no good. One by one or all at once, families disappeared and were separated in the ordeal of Nazi Germany in 1941. We never saw Aunt Kate, Aunt Friede, or Aunt Elsbeth again.

TRAPPED IN HITLER’S HELL

By Anita Dittman with Jan Markell

“It was early that spring, in a Nazi roundup that I learned just how precarious our lives were. I was living in the ghetto with my widowed mother and my grandmother. There were two adjacent hiding places: one was in a storage area, the other in a room you couldn’t see from the outside. As the roundup started, all the Jews in the area started running toward those hiding places. My mother and I were going toward the room you couldn’t see. Suddenly she grabbed me. I don’t know why she changed her mind, but she pulled me over to the storage area instead. We waited, breathless, as the Ukrainian police ran past. Moments later there was shouting and banging next door as the other hiding place was discovered. As the Jews filed out, one man who had just been captured yelled out to the police, ‘There are people in there too!” I could see through a crack in the wall that he was pointing to the place where we were hiding. Terrified, I would certainly have screamed if my mother hadn’t clapped her hand over my mouth. I stood shaking as the police began pounding on the wall – our wall! Plaster dust was flying, which made the police cough. But the wall was solid; it didn’t give way. Another few minutes and we would have been finished. Luckily for us the police gave up. It was too much trouble! ‘That Jew just lied to make us work,’ one of the Ukrainian policemen muttered disgustedly as they walked away. My knees buckled with relief. We’d made it! But if I felt even a little bit invincible that day, it wasn’t to last. Two weeks later it was Purim, a Jewish holiday of joy and celebration. My mother and her cousin and two other women had just left on their way to work when an SS officer with a huge police dog stopped them. He arrested all four of them for no special reason. He took them to the local headquarters, made them undress, and then he shot them to death. That night my grandmother told me what had happened. She hugged me and she said, ‘Don’t ever forget you were very important to your mother.’ That night I lay in bed terrified, wondering what would happen next.”

THE HIDDEN CHILDREN

By Jane Marks

Children who were rounded-up in the Lodz ghetto, march towards a deportation to a death camp where they will be killed by gassing.

“I gave birth to a beautiful girl, whom the midwife said she would wash. But there was no hot water, no clothes, no diapers, no soap – nothing. I wrapped the baby in my prisoner’s clothes and a blanket, now soaked with blood. In the morning Mengele checked the baby and ordered my breast bound with a makeshift bandage. I was forbidden to breast-feed. The nurse bound my breasts and the baby cried terribly. A woman working in the depot stole a nightgown and gave it to me as a present. From it I made four diapers. We were given bread and soup. I put some bread in a piece of the diaper and dipped it in the soup. That’s what I fed my baby. I was filled with milk, but I didn’t dare unbind my breasts. The baby cried nonstop, but her cries lessened each passing day. Mengele came in daily to check on the baby. He talked politely to me and then left. I lay there for six or seven days, my belly swollen and wounds on my body. Mengele came in and said, `Tomorrow you will be ready. I will take you and the baby.’ I knew my baby and I would be sent to the gas chamber, but I was young and wanted to live, so I cried and could not sleep. I was screaming in the evening when suddenly a Czech doctor came in. She was a prisoner like me and asked matter-of-factly what I was screaming about. I told her we would be sent to the gas chamber the next day. She said, ‘I will help you.’ When she came back she said, ‘I brought you something. Give it to your baby.’ It’s a syringe. When I asked what was in it she said casually, ‘Morphine. It will kill your baby.’ I was amazed. ‘You want me to kill my baby!’ She spoke with a voice of an angel, saying she had to save me. I told her to administer the syringe, but she refused, citing her Hippocratic Oath and telling me the baby could not survive, and she had to save me. I finally injected my baby. It took a long time but she stopped breathing and they took her away. I did not want to continue living. In the morning Mengele asked for the girl I but I told him she had died during the night. He ran outside, where they collected the dead bodies, but didn’t find her tiny corpse. When he returned, he said I was lucky because I would leave Auschwitz in the next transport. I didn’t care. I didn’t want to live after what I had done.

OUR CRIME WAS BEING JEWISH

By Anthony S. Pitch

For around 6,500-7,000 Jews, rounded up from subsidiary camps in East Prussia of Stutthof concentration camp (itself located in West Prussia), hastily closed down on 30-21 January as the Red Army approached, scarcely conceivable days of terror began as they were marched off…in horrific conditions to reach Konigsberg… Many Jews were shot even on the way to Konigsberg. Still more were killed, their bodies left on the streets of the East Prussian capital, as the death march to Palmnicken began. The remainder were herded off, clothed in little more than rags and wooden clogs. Though hardly able to walk on the snow and ice, any Jews lagging behind or falling down were shot. The guards killed more than 2,000 on the 50-kilometer march from Konigsberg to Palmnicken, leaving the bodies by the roadside. Some 200-300 corpses were found on the last stretch of little over a kilometer as the remaining 3,000 or so prisoners straggled into Palmnicken on the night of 26/7 January… That same evening, the local mayor, a long-standing and fanatical member of the Nazi Party, summoned a group of armed Hitler Youth members, plied them with alcohol and sent them along with three SS men, who were to explain the task ahead…The boys were left to guard around forty to fifty Jewish women and girls who had earlier tried to escape, until they were taken out, in the dim light of a mine-lamp, to be shot by a group of SS men, two by two. The Soviets were though by this time to be very close. The SS men were anxious to “get rid of the Jews no matter how.” They decided to solve their problem by shooting the rest of their captives.

The following evening, 31 January, the improvised massacre took full shape. Shielded from the village by a small wood, the SS men, their flares lighting up the sky, drove the Jews onto the ice and into the frozen water using the butts of their rifles and mowed them down on the seashore with machine guns. Corpses were washed up along the Samland coast for days to come… About 200 of the original 7,000 survived.

THE END

By Ian Kershaw

On the morning of September 1, 1933, a Friday, H. V. Kaltenborn, the American radio commentator, telephoned Consul General Messersmith to express regret that he could not stop by for one more visit, as he and his family had finished their European tour and were preparing to head back home. The train to their ship was scheduled to depart at midnight. He told Messersmith that he still had seen nothing to verify the consul’s criticism of German and accused him of “really doing wrong in not presenting the picture in Germany as it really was.” Soon after making the call, Kaltenborn and his family – wife, son, and daughter – left their hotel, the Adlon, to do a little last-minute shopping. The son, Rolf, was sixteen at the time. Mrs. Kaltenborn particularly wanted to visit the jewelry stores and silver shops on Unter den Linden, but their venture also took them seven blocks farther south to Leipziger Strasse, a busy east-west boulevard jammed with cars and trams lined with handsome buildings and myriad small shops selling bronzes, Dresden china, silks, leather goods, and just about anything else one could desire. Here too was the famous Wertheim’s Emporium, an enormous department store – a Warenhaus – in which throngs of customers traveled from floor to floor aboard eighty-three elevators. As the family emerged from a shop, they saw that a formation of storm troopers was parading along the boulevard in their direction. The time was 9:20 a.m. Pedestrians crowded to the edge of the sidewalk and offered the Hitler salute. Despite his sympathetic outlook, Kaltenborn did not wish to join in and knew that one of Hitler’s top deputies, Rudolf Hess, had made a public announcement that foreigners were not obligated to do so. “This is no more to be expected,” Hess declared, “than that a Protestant cross himself when he enters a Catholic Church.” Nonetheless, Kaltenborn instructed his family to turn toward a shop window as if inspecting the goods on display. Several troopers marched up to the Kaltenborns and demanded to know why they had their backs to the parade and why they did not salute. Kaltenborn in flawless German answered that he was an American and that he and his family were on their way back to their hotel. The crowd began insulting Kaltenborn and became threatening, to the point where the commentator called out to two policemen standing ten feet away. The officers did not respond. Kaltenborn and his family began walking back toward their hotel. A young man came from behind and without a word grabbed Kaltenborn’s son and struck him in the face hard enough to knock him to the sidewalk. Still the police did nothing. One officer smiled. Furious now, Kaltenborn grabbed the young assailant by the arm and marched him toward the policemen. The crowd grew more menacing. Kaltenborn realized that if he persisted in trying to get justice, he risked further attack. At last an onlooker interceded and persuaded the crowd to leave the Kaltenborns alone, as they clearly were American. The parade moved on. After reaching the safety of the Adlon, Kaltenborn called Messersmith. He was upset and nearly incoherent. He asked Messersmith to come to the Adlon right away… “It was ironical that this was just one of the things whicn Kaltenborn said could not happen,” Messersmith wrote later, with clear satisfaction. “One of the things that he specifically said I was incorrectly reporting on was that the police did not do anything to protect people against attacks.” Messersmith acknowledged that the incident must have been a wrenching experience for the Kultenborns, especially their son. “It was on the whole, however, a good thing that this happened because if it hadn’t been for this incident, Kaltenborn would have gone back and told his radio audience how fine everything was in Germany and how badly the American officials were reporting to our government and how incorrectly the correspondents in Berlin were picturing developments in the country.”

IN THE GARDEN OF BEASTS

By Erik Larson

Although by now there were more than 1,000 people in the gas chamber, more were obviously expected. In fact, before long a third convoy of trucks moved into the yard. Once more the people were driven into the changing room with the utmost brutality. After a while, I heard the sound of piercing screams, banging against the door and also moaning and wailing. People began to cough. Their coughing grew worse from minute to minute, a sign that the gas had started to act. Then the clamor began to subside and to change to a many-voiced dull rattle, drowned now and then by coughing. The deadly gas had penetrated into the lungs of the people where it quickly caused paralysis of the respiratory center… Even before the bottom bar had been unbolted, both wings of the double doors were bulging to the outside under the weight of the bodies. As the doors opened, the top layer of corpses tumbled out like the contents of an overloaded truck when the tail-board is let down. They were the strongest who, in their mortal terror, had instinctively fought their way to the door, the one and only way out, had there been even the remotest possibility of getting out. It was the same every time the gas chamber was used. Moreover, the bodies were not evenly distributed throughout the chamber; most of them lay in heaps, the largest of which was always by the door. The spot where the gas came in was practically empty: no doubt the people had moved away from these places because the gas smelled of burning metaldehyde and had a sickly-sweet taste. After a short time, it produced an excruciating irritation of the throat and intense pressure in the head, before it took its lethal effect. We had orders that immediately after the opening of the gas chamber we were to take away first the corpses that had tumbled out, followed by those lying behind the door, so as to clear a path. This was done by putting the loop of a leather strap round the wrist of a corpse and then dragging the body to the lift by the strap and thence conveying it upstairs to the crematorium. When some room had been made behind the door, the corpses were hosed down. This served to neutralize any gas crystals still lying about, but mainly it was intended to clean the dead bodies. For almost all of them were wet with sweat and urine, filthy with blood and excrement, while the legs of many women were streaked with menstrual blood.

EYEWITNESS AUSCHWITZ

By Filip Muller

The American troops were confronted by scenes of horror they had never imagined possible. In his official report, Brigadier General Henning Linden, the assistant division commander described what the first glimpse of Dachau was like: “Along the railroad running along the northern edge of the Camp, I found a train of some 30-50 cars, some passenger, some flatcars, some boxcars all littered with dead prisoners – 20-30 to a car. Some bodies were on the ground alongside the train, itself. As far as I could see, most showed signs of beatings, starvation, shooting, or all three.” In a letter to his parents, Lieutenant William J. Cowling, Linden’s aide, described what he saw in more graphic language: “The cars were loaded with dead bodies. Most of them naked and all of them skin and bones. Honest their legs and arms were only a couple of inches around and they had no buttocks at all. Many of the bodies had bullet holes in the back of their heads. It made us sick to our stomach and so mad we could do nothing but clench our fists. I couldn’t even talk.”

THE NAZI HUNTERS

By Andrew Nagorski