“The next morning, we arrived in Debrecen [Hungary], where the gendarmes were concentrating the Jewish people from the smaller ghettos before deporting them somewhere else by train… They beat people, punishing them for even the slightest infraction. On the first day I saw one of the oldest people from my town, a man I knew who was very hard of hearing, feeble and near-blind, walking with a white cane in the middle of the yard where freight cars stood with open doors. While he shuffled around in the yard, a guard yelled at him to stop, but since he didn’t hear, he kept walking. After the third yell, they grabbed him, beat him and hung him up by his wrists from the corners of one of the freight car’s doors. He lost consciousness within minutes and they didn’t even take him down. They left him there to show others what would happen to those who didn’t obey orders. They did this only because we were Jews.”

A TRAIN NEAR MAGDEBURG

By Matthew A. Rozell

One day I was able to have a last conversation with a small group of Jewish families who had been caught. For four months, so they told me, they lived in dug-outs near Sosnovits, leaving their hiding-places only at night to get a breath of fresh air and also provide themselves with the bare necessities of life. When their money ran out, their supplies dried up too. Hunger and thirst, cold and disease, took them to the brink of despair. In the end they were given away by the constant crying of their hungry and feverish children. SS patrols who were always prowling around with their dogs tracked them down. Without questioning or trial they were brought to Birkenau from where there was no return. They were exhausted and on the point of collapse, and they knew full well what was in store for them.

EYEWITNESS AUSCHWITZ

By Filip Müller

“We stood at the entrance of the house. Father was to leave me there and go off. He was pale and had a tormented look. He could not move. He hugged me, kissed me and went off. He came back a moment later, and we embraced again. I did not cry. I clung to him. Again he left. No, I saw him come back once more. I felt I wanted him to leave; I couldn’t bear it any longer. ‘Daddy, goodbye, see you again. You’d better go!’ One more hug, and he left. Left altogether. A long time has passed since I saw him disappearing into the distance, turning again and again to look at me. I was naïve enough to believe we would see each other in a week’s time. I did not know, nor did Father, that at that very moment the order to surround the ghetto before the final liquidation was already in the works.”

A TRAIN NEAR MAGDEBURG

By Matthew A. Rozell

All of the Jews of Mielec [southeastern Poland] were collected in the Large Market amid shouts and shooting. There were selections: Young men were lined up – we didn’t know for what purpose at the time – old men were taken away, their bundles left behind in a pile. And others, we among them, were soon driven like an enormous herd of cattle along the road that cuts diagonally across the Large Market. Eyes behind lace curtains, half concealed faces behind closed windows, silently watching the moving, seething, running, stumbling dark clad mass of people, urged on by Germans who blindly hit us and shot into the mass, pulled out men and women, lining them up in a field to be shot when Mielec had receded in the distance for the rest of us. How many died that morning in the field, killed by men turned monsters, I shall never know.

THE CHOICE

By Irene Eber

Pictured in the front row are Karl Hoecker, Otto Moll, Rudolf Hoess, Richard Baer, Josef Kramer (standing slightly behind Hoessler and partially obscured), Frannz Hoessler, Josef Mengele [directly left of the accordionist’s head] and Walter Schmidetzki. Most escaped justice.

“Utter chaos and scenes of horror greeted the British and Canadian soldiers who walked into the hell that was Bergen-Belsen. Soldiers were now face-to-face with 60,000 prisoners who were in various states of starvation and illness – many of whom, surrounded by thousands of corpses, were in the final throes of death themselves. Eight hundred died on the day of liberation, and 14,000 more would die in the weeks to follow.”

A TRAIN NEAR MAGDEBURG

By Matthew A. Rozell

The internees in our camp totaled from thirty to forty thousand. And the entire personnel in our infirmary consisted of five women! Needless to say, we were swamped with work. We rose at four in the morning. The consultations began at five. The sick, of whom there were often as many as fifteen hundred in a day, had to wait their turns by rows of five. It was pitiful to behold these columns of ailing women, scantily clad, standing humbly in the rain, snow, or frost. Often when their last strength ebbed, they fainted like so many tenpins falling.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

When the doors were opened, the guards bellowed, “Get out! Get out, you scum! Move! Move!” They slammed their rifle butts into the Jews’ backs. Some could barely walk. Others tumbled out. “Men and older boys to the right! Women, children, and the old to the left!”… Eddie and Israel moved to the right and watched those in the left column disappear through a large gate. Why are so few people coming out of the cars? He wondered. They were packed. Eddie got his answer minutes later when he and the other young men were ordered to remove the dead from the cattle cars. In every car he found bodies. He was beyond shock, beyond despair. It was too hard for his brain to process. Here was the body of the baker and over there, that of a neighbor. Oh, God, no. Not Esther. And her whole family. Eddie’s cousin Esther Yocheved, her three young daughters, and her husband were curled up together, dead. Lying nearby he spotted the bodies of Uncle Matis and his wife and daughter.

ESCAPE

By Allan Zullo

I was about 7 years old when World War II broke out. We were a happy family with three children. My sister, Gizia, was three years older than me and my sister Sarenka was about five years younger (she was a year old when the war began). I was nicknamed “Leosz” which stood for my formal name – Leon. My mother took care of the house and kept busy with all sorts of social activities. I remember her as always being beautiful and radiant, dressed in the best of taste, and always concerned about her appearance. Like every good Jewish Pole she was very proud of her children and would habitually boast about our amazing exploits. Financially, we were in the upper middle class. The horrific war burst into this good and happy life and after an unbearable six years of going through all the levels of hell, my whole family – parents, sisters, 16 aunts and uncles and 23 cousins – were all murdered, and only I survived.

I ONLY WANTED TO LIVE

By Arie Tamir

The prisoners, a total of about 10,000 people, had all been murdered between November 3rd and 5th of 1943, as part of the Harvest Project. They had been led, naked, to pits that had been dug in advance outside of the camp, where they were shot, their bodies falling into the pits, bleeding and choking among the bodies of those that preceded them, and finally buried alive under the bodies of those that followed. The pits and the dying people inside them were then set on fire.

RAKING LIGHT FROM ASHES

By Relli Robinson

On November 5, 1943, on a single terrible day in the Shavl ghetto [Lithuania], a roundup of children had occurred there. Soldiers with snarling dogs and bayonets had rampaged through the narrow streets, ripping apart walls and floors in the search for every last child. A Jewish policeman stood at the ghetto gate as the sons and daughters of the ghetto – hundreds of them – were shoved into trucks and driven away, never to be seen again.

WE ARE HERE

By Ellen Cassedy

We expected our father to be at home, but we could not find him. No matter where we inquired, nobody could tell us his whereabouts. His disappearance became our main concern. We prayed and hoped that our father would eventually show up. In November 1939, a member of the Judenrat, (Jewish Community Council) told my stepmother that at the outskirts of our town, in Trzebina [Poland], there was a pit of unidentified victims. Thirty-eight people were picked up at random and were shot. My father was shot on September 11, 1939. He was left to bleed to death. One of those captives pretended to be dead, and managed to escape during the night. Thirty-seven victims were thrown into a pit. They were murdered for no other reason than to sow fear, panic, and subjugation among the populace, especially the Jewish inhabitants. That crime was committed by some cruel, heartless, and callous Deutsche Wehrmacht (soldiers of the German army).

FROM A NAME TO A NUMBER

By Alter Wiener

The cruelty of the SS guards first became apparent in the shower room. While we were washing, a soldier stood by one of the big wheels that controlled the temperature. For sport, he turned it on to scalding. As we tried to jump away to avoid getting burned, another soldier with a truncheon would beat us to get back under the flow. Then the first soldier turned the water freezing cold. A young man who was showering with us held his eye glasses in his hands. They had very thick lenses and he was obviously short-sighted. The rush of water washed his glasses right out of his grasp, and when he got down to his knees to try to find them, a guard came over and kicked him in the side of the head with his jackboot. The young man rolled over and the guard stomped on his chest. I could hear the cracking of ribs. The guard who was now in a frenzy, continued to stomp on the man until he was dead…This was my initiation to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

BY CHANCE ALONE

By Max Eisen

All of the Jews of Mielec [southeastern Poland] were collected in the Large Market amid shouts and shooting. There were selections: Young men were lined up – we didn’t know for what purpose at the time – old men were taken away, their bundles left behind in a pile. And others, we among them, were soon driven like an enormous herd of cattle along the road that cuts diagonally across the Large Market. Eyes behind lace curtains, half concealed faces behind closed windows, silently watching the moving, seething, running, stumbling dark clad mass of people, urged on by Germans who blindly hit us and shot into the mass, pulled out men and women, lining them up in a field to be shot when Mielec had receded in the distance for the rest of us. How many died that morning in the field, killed by men turned monsters, I shall never know.

THE CHOICE

By Irene Eber

Fifteen year old Alicia Jurmann and others were taken 20 miles to a prison in nearby Chortkov, Poland, where the Gestapo had its regional headquarters. When the captives arrived, SS men barked orders and insults, yanking people off the sleighs and beating them with sticks and rifle butts. Seeing a woman fall from a blow to the neck, Alicia helped her to her feet. But this act of kindness infuriated an SS man, who whacked Alicia so hard with a bamboo ski pole that knocked the breath out of her. He beat her again and again until the pole snapped in two and she crumpled to the ground. “Dirty Jew!” he screamed, kicking her with his heavy boots until she heard several ribs crack. A captive who was a family friend helped walk the injured girl into the prison. All the women were ordered to take off their winter coats and throw them in a pile and remove all their jewelry. When Alicia couldn’t get an earring off fast enough, an SS officer angrily yanked it off, tearing her earlobe. As blood flowed down her cheek, Alicia fearlessly berated him. “How dare you call yourself an officer,” she snapped. “My father was a decorated hero in World War One and an officer and a gentleman. You are a disgrace to the uniform.” Releasing her anger felt good – until the SS officer and his comrades brutally beat her and kicked her into unconsciousness. She woke up in terrible pain the next morning in a crowded, freezing cell.

ESCAPE

By Allan Zullo

Jewish deportees, carrying a few personal belongings in bundles and suitcases, march through town from the assembly center at the Platzscher Garten to the railroad station. [Wuerzburg, Germany] Almost all would be murdered through gassing at Auschwitz or starvation at Thersianstadt.

If the first deportation [from Krakow] took place in comparable quiet, without violence on the part of the Germans, this second round brought in an SS unit that was extremely cruel and aggressive. Mercilessly, they beat people as they walked to the trains as well as in the square itself. Many were injured and killed. There was torture just for torture’s sake, and they robbed the Jews as they went, so many were forced onto trains without even the little they had been allowed to take. From June 2nd and on, it was impossible to go outside without risking arrest and deportation, even if you had all the proper authorizations – and that’s how the worst happened to us: Grandma, Aunt Fela and her two young children, little David and his wife, and Dad’s sister Genia were caught and sent away. This apparently happened on the very first night of the second round of deportations. We only found out about it a day or two later. Mom shut herself up in her room and couldn’t stop crying.

I ONLY WANTED TO LIVE

By Arie Tamir

The persecution aimed at the Jewish community [Poland] brought vulnerability and dysfunction. Very few Jewish women gave birth. Many children were inflicted with rickets due to an inadequate intake of vitamin D. we all withered on meager food rations. Jews had to wear an armband with a blue Star of David. Later, it changed to a yellow Star of David. It was a crime if a Jew failed or rather, forgot to wear it. New rules forbade us to live, or even walk through certain sections of the town. We were ordered to take off our caps or hats and bow to any passing German. Nobody dared to raise a voice in protest. Everybody was bowed down, prostrated, and stifled. There was no other voice except the brutal German’s voice. The abominable decrees construed an attack upon the principles of a civilized society – a disgrace to humanity! Life was hardly bearable, a melancholy permeated all. However, nobody had any clue of the ominous days yet to come. In March 1940, I was shoveling snow in front of our house. I did not take off my cap when a German policeman passed by, because I had not noticed him. “I am so sorry. I am just a little Jewish kid.” I implored, but he mercilessly beat me. He could have killed me without any compunction. I was afraid to look at his face.

FROM A NAME TO A NUMBER

By Alter Wiener

I ran to a fenced-off holding area where the SS kept the selected prisoners until they were ready to transport them to Birkenau to be gassed. I saw many people milling around inside this area, and I called the names of my father and uncle. Within seconds, they came to meet me at the barbed-wire fence. I was so happy to see them, but at the same time, I knew these were likely our last moments together. I didn’t have any words. I couldn’t express a single word of consolation or hope. The guard from the tower yelled, “Move away from the fence immediately or I will shoot you!” My father reached out across the wire and blessed me with the classic Jewish prayer: “My God bless you and safeguard you. May He be gracious unto you. May He turn His countenance to you and give you peace.” This was the same prayer my father once uttered to bless his children every Friday evening before the Sabbath meal. Then he said, “If you survive, you must tell the world what happened here. Now go.” As I walked away, I took one final look before I turned the corner of the building and was unable to see them any longer.

BY CHANCE ALONE

By Max Eisen

We ran and stumbled along this road [to Berdechow], deaf to everything except the German shouts, gunfire, the screams of the wounded and dying. We ran in fear for our lives, clinging to one another lest we lose sight of each other, not knowing who would be next to fall, to lose his life, to be pulled out of the running, stumbling mass and singled out for murder… In a history book, the fate of the Mielec Jews merits a brief, inaccurate paragraph “…the action was carried out, with marked brutality and cruelty, from March 7 to 9. Large numbers of Jews were shot on the streets of the town, and in the airfield nearby. The remaining Jews…were deported to different localities in the Lublin district.” The historian does not know that the Aktion lasted only one day, nor is he able to describe what death and fear of death are like.

THE CHOICE

By Irene Eber

Two days after the Kristallnacht [1938] Ernst Cramer, twenty-three, was fighting for breath among the dazed men jammed into a truck headed from the Weimar railroad station to the Buchenwald concentration camp. The truck normally held twenty-eight. That morning more than sixty Jews aged eighteen to twenty had been herded into the vehicle by SS men swinging truncheons, steel rods, and rifle butts… For all of November 12, Ernst Cramer, his father, and the other new Buchenwald arrivals stood, immobile as statues, on the muddy parade ground. Whoever moved was beaten by rubber truncheons or hung from posts by the hands, handcuffed in back. When the weak collapsed, other prisoners dragged them to the washhouse, which that day became a mortuary. At nightfall the new prisoners, over 10,000 of them, were driven into five makeshift barracks. Some had to sleep on top of others. “During the night many went crazy and suffered from fits of raving,” Cramer remembered. Two were drowned by guards in the latrine. The next morning Ernst was assigned to the detail that carried the dead into the former washhouse.

STELLA

By Peter Wyden

In the morning [Auschwitz], we had to be content with rinsing the bowls as well as we could before we put in our minute rations of beet sugar or margarine. The first days our stomachs rose up at the thought of using what were actually chamber pots at night. But the hunger drives, and we were so starved that we were ready to eat any food. That it had to be handled in such bowls could not be helped. During the night, many of us used the bowls secretly. We were allowed to go to the latrines only twice each day. How could we help it? No matter how great our need, if we went out in the middle of the night we risked being caught by the SS, who had orders to shoot first and ask questions later.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

The Jews arrived at the ghetto in the town of Siedlce. Everywhere he looked in the evening light, Eddie saw bodies lying in the streets. The gruesome sights made him forget about his unquenchable thirst. The marchers were herded into a barbed-wire pen for the night – which turned into a night of terror as German troops callously shot into the crowd. Eddie and Israel huddled together hearing the screams of the wounded and dying, who had been caught in the line of fire. At dawn, Eddie saw dozens of bodies of Jews carried out and placed on carts. They had been killed during the night. He warned his brother not to do anything to attract attention because the guards were still shooting people who caught their eye – a man with a red beard, a girl in a colorful dress, a boy playing with a stick. And with every murder, the guards laughed. The sun beat down on the parched captives, all craving a drink of water. But none was given. Late in the afternoon, they were marched to the railroad station. To ease their awful thirst, some scooped mud from puddles alongside the road and stuffed it in their mouths. A bullet put an end to their thirst and their lives. Others who broke ranks sprinted toward nearby wells were cut down by gunfire.

ESCAPE

By Allan Zullo

One evening after putting Sarenka [age 4] to bed, our parents told us that they intended to give Sarenka to Uncle David, who had Nicaraguan citizenship and lived outside the ghetto. They would officially adopt her and register her as their daughter. Our parents swore us to secrecy about this plan… I never saw my little sister again. Uncle David’s family lived in Krakow until 1944, when they were deported to Bergen-Belsen in Germany. That camp was where the Germans collected all civilians with foreign passports. They lived there until the beginning of 1945. My knowledge of what happened to my sister and my uncle’s family came from two families who were in Bergen-Belsen with them and survived the war. They told me that several weeks before the war ended, the Germans took 50 families from the camp and murdered them – and my family was in this group. Just a few weeks before they would have been free, the Germans killed my sweet little sister, only seven years old; and my cousins Lusia (17) and Genia (23). I never managed to learn how they were killed or why specifically this group was killed (most of those holding foreign citizenship who were in Bergen-Belsen survived). I try to imagine how my sister looked at age seven, how they killed her, if she cried, if she suffered, if there was someone to hug her as they murdered her… To this day I cannot imagine how they could kill my little seven-year-old sister, and another million and a half children. How could such a thing happen?

I ONLY WANTED TO LIVE

By Arie Tamir

In June 1942, in the middle of the night [Chrzanow, Poland], Nazis barged into our home. A young soldier with a smug smile shouted at me, “Du knabe (youngster), come with us. You have five minutes to get ready.” I remember my eight-year-old brother crying, and clinging to his mother’s apron. She momentarily held me close and sobbingly said, “I love you so much, my good soul.”

FROM A NAME TO A NUMBER

By Alter Wiener

I felt a blow on the back of my head. Although I did not feel any pain, there was a buzz in my ears and a feeling of dizziness overcame me. When I tried to pick up my shovel to resume working, I felt something warm dripping down my neck and I saw blood. I turned around to see an SS guard standing behind me, and I realized that I had received a blow from the butt of his gun. Our eyes locked for a second and I saw his twisted, evil grimace. I thought I was looking at the devil. Blood continued to pour from the wound, and I went into shock and collapse. The other prisoners hauled me out of the pit and threw me into a nearby ditch to keep me out of the way until the end of the day… I was simply written off. At some point, Kommandant Kuntz probably received a report that our unit was down one prisoner, and he came to have a look at me. I thought he would pull his pistol from his holster and shoot me on the spot. Instead, he signaled with his right hand, his finger pointing up in a circular motion, meaning that I was going to go up the chimney of the crematorium. I understood my fate was sealed. A feeling of helplessness and fright overtook me. How could I prepare myself to face the gas chamber? I would be reduced to a simple pile of ashes. I had always planned, as a last resort, to run to the electrified fence and die by my own action, but this was no longer an option because I had lost my mobility. I began to wish that the Kommandant had put a bullet in my head. I thought of my family and how they must have felt while facing their own demise. When my mother entered the gas chamber, she had my three siblings in her care. How she must have fought until the last breath in that horrible chamber. What would it be like for me? Slow or fast? Would my soul leave my body? Would I meet my family again? Would they all be waiting for me? How would I know them? What shape or form would they be in? I felt utterly alone, with no one to take care of or comfort me. No one could save me.

BY CHANCE ALONE

By Max Eisen

Horrible scenes took place within the gas chamber, although it is doubtful if the poor souls suspected even then. The Germans did not turn on the gas immediately. They waited. For the gas experts had found it was necessary to let the temperature of the room mount by a few degrees. The animal heat given off by the human herd would facilitate the action of the gas. As the heat increased, the air fouled. Many of the condemned were said to have died before the gas was turned on. On the ceiling of the chamber was a square opening, latticed and covered with glass. When the time came, an SS guard, in a gas mask, opened the peephole and released a cylinder of “Cyclone-B,” a gas with a base of hydrate of cyanide which was made at Dessau. Cyclone-B was said to have a devastating effect. Yet this did not always happen, probably because there were so many men and women to kill that the Germans economized. Besides, some of the condemned may have had high resistance. In any case, there were frequently survivors; but the Germans had no mercy. Still breathing, the dying victims were taken to the crematory and shoved into the ovens.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

The worst moments were Dr. Mengele’s “special selections.” Women had to remove their clothes while he looked them over to see if they were still healthy enough to work. He would move his little baton in a circular motion to indicate to the petrified prisoner to turn around so that he could inspect her backside. Then, with a tap of his baton, he would pick out the ones for the gas chamber. For Hanci, the crushing anxiety that he would select her mother or sister – or herself – nearly squeezed the air out of her lungs. While they stood in line waiting for his life-or-death decisions, many prisoners crumbled under the tension and fainted. They were dragged away and gassed.

ESCAPE

By Allan Zullo

Corpses piled in the crematorium mortuary [at Dachau]. These rooms became so full of bodies that the SS staff and survivors began piling corpses behind the crematorium, where they were found by U.S. troops.

The daily menu of the prisoners [Gestapo Prison – Stanislawow, Poland] consisted of black coffee and two pieces of black bread for breakfast, a bowlful of hot water with three or four cabbage leaves floating on top for lunch, and some more bitter black coffee for supper. This prison fare got us into such a weakened state that we could hardly stand on our legs. After drinking all this liquid we spent most of the night running to the toilet. One night I counted 22 “runs” as my personal record. So there was little chance for sleep that night, and just as little during the day, because sleeping in the day time was considered a punishable offense.

AMONG MEN AND BEASTS

By Paul Trepman

Major Haase, who had overseen the deportation, was very pleased by the “Action” [deportation from Krakow]. About 4,000 Jews had been deported from the ghetto, just as the Nazis had planned…This time, the Nazis didn’t try to trick anyone or cover up their deeds. They didn’t tell stories about transferring people to work in the East. It was clear that those who were put on the trains were going to their deaths, for the emphasis was on getting rid of as many of the children, the elderly, the sick, the crippled, and the least useful ones, as possible. The entire orphanage, with its 300 children and 20 staff, were taken to the trains. The old age home was emptied of its sick and terminal residents. And each and every person in the hospitals – patients and doctors alike – was deported. Many of the patients were even shot and killed inside the hospitals. As the Nazis had threatened, on that morning after 10:00, every person found in their homes instead of the street was shot and killed – and so 600 more Jews were murdered in addition to the 4,000 taken to the gas chambers in Belzec.

I ONLY WANTED TO LIVE

By Arie Tamir

The market remained as if asleep until suddenly the silence was shattered by the crude sound of motorcycles and the terror-stricken cries of a great and still-invisible multitude. The deportation from Radomysl Wielki [Poland] and the surrounding villages had begun. Its course was similar in broad outline to the deportation from Mielec, yet different. Again the Jews were collected in the market-place – those who were driven in like so many cattle from the outlying areas and those who lived in the town. But instead of being marched away, the people were made to stand in a tightly packed mass to witness the house searches for hidden Jews, the “flushing out,” as it was called. We stood in the marketplace under the hot noon sun watching the horror unfold, as if invited to witness a macabre performance in which for a time at least we were spectators and not the performers. Loudly shrieking, crazed men covered with blood ran from the circles in the market until they fell and did not move again. Babies were flung from windows, landing with a thud on the gray cobblestones. Gunfire echoed through the narrow alleys behind the market as more and more people were found hiding. They ran here and there like frightened animals, thinking perhaps they could dodge the Germans bullets; their shrill screams reverberated in the alleys and market. Walls were smashed and doors broken down in search of hiding places. When finally these noises ceased, we, the masses in the marketplace, were once again assigned a part in the performance. We were made to stand in straight lines and then counted. Every tenth person was taken out and killed.

THE CHOICE

By Irene Eber

Deportees [from Berlin] walked in darkness, however, usually driven to the doors in the anonymous closed furniture vans preferred by the Gestapo to hide their efforts from the civilians. The coyness was futile. The synagogue towered over the corner of Jagow Strasse, an always busy intersection near the NW 87 post office. Its camp was the first of the Holocaust’s Nazi secrets that were no secrets. Who could overlook the trudging, silent queues of families bent by rucksacks and overstuffed suitcases? … They lined up to pass by long tables behind which clerks had set up large laundry baskets that kept filling rapidly. “Work papers, bread coupons, tax documents, and money had to be handed over,” remembered one of the deportees, Dr. Karl Loesten. “Then came a body search, and after that the luggage was ransacked and shamelessly robbed.” Jewelry was taken, as well as any remaining money, and soap, and chocolate or other bits of food or alcohol. Then came a final bureaucratic stab. “A court bailiff handed me a document,” said Dr. Loesten, “declaring that all my assets had been confiscated because I was an enemy of the State.” The Nombergs learned that they would leave in two or three days. Their destination would be Litzmannstadt (Lodz), Poland. Word had circulated for some time about wholesale deaths there, mostly from starvation.

STELLA

By Peter Wyden

Not until two days after we were established [at Auschwitz] did we receive our first morning meal – nothing except a cup of insipid, brownish liquid, presumptuously called “coffee.” Sometimes we were given tea. To tell the truth, there was no ascertainable difference between the two beverages. They were not sweetened, yet they were our whole meal, without even a crumb, to say nothing of a crust of bread. At noon we had soup. It was difficult to say what ingredients went into that concoction. Under normal conditions, it would have been absolutely inedible. The odor was sickening. Often we could eat our portions only by holding our noses. But it was necessary to eat, and somehow we overcame our disgust. Each woman swallowed her share of the contents of the bowl in one long draught – of course, we had no spoons – like children swallowing bitter medicine.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

The Jews had been lined up in four rows around the pile of coal that was kept there for the prison kitchen. We saw one of them, a tall, heavy-set, black-haired man, holding a huge red flag in his hand. Gestapo men were running up and down between the four lines, beating the unfortunates with their whips. At a barked command, the Jews undressed and the men and women stood there together, naked, while Oskar Brand strolled about casually, lashing out to the right and to the left with his whip. One after the other, the Jews ran over to the coal pile, dropping their clothes and their last possessions – money, watches and whatever other small articles had not been taken from them at the time of their arrest. As they ran back to their places, the Gestapo men hurried them along with cuffs, blows and kicks. The faces of the helpless Jews were as white as chalk; all the blood seemed to have drained from them… When we looked out again sometime later, we saw the Jews being marched away. Soon, we heard shots from somewhere in in the distance – one shot after the other. The next morning, the Ukrainians in our labor detail told us what had happened. The Jews had been loaded onto the trucks, row upon row, first men, then women, then men again, thirty-six at a time, like so many living corpses, and driven to the Jewish cemetery which was not too far from the prison. There, they were shot to death. We figured out that at least 300 Jews must have been killed on that one day.

AMONG MEN AND BEASTS

By Paul Trepman

Although I worked at the infirmary, for a while I also had to help carry the corpses from the hospital… At the entrance to the morgue we set down the stretcher and dragged the corpses inside. We simply added them to the pile of dead. We perspired heavily but dared not wipe our faces with our contaminated hands. Of all the horrible tasks I had to do, this one left me with the ghastliest memories. I refuse to elaborate further to describe how we had to trample over the accumulations of rotting, putrid cadavers, many of whom died from frightful diseases.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

“They shot many people in Auschwitz. They used to count to ten. They took the tenth person with no questions asked. I saw them shoot that person in front of us.”

OUR CRIME WAS BEING JEWISH

By Anthony S. Pitch

When the first Soviet soldiers appeared at the gates of Birkenau, some prisoners ran toward them. “We hugged and kissed them,” Otto Wolken said a few months later, “we cried with joy, we were saved.” Elsewhere in the Auschwitz complex, however, fate took a last terrible twist. On the same day Birkenau was liberated, SS terror struck in the satellite camp Furstengrube, just twelve miles farther north. The camp SS had abandoned the compound eight days earlier, leaving some 250 sick prisoners to fend for themselves. On the afternoon of January 27, 1945, a group of SS men suddenly entered the camp and slaughtered almost all the inmates. Only some twenty prisoners lived to see the Red Army arrive; they had come through the last massacre in Auschwitz.

KL – A HISTORY OF THE NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS

By Nicolaus Wachsmann

The persecution aimed at the Jewish community [Poland] brought vulnerability and dysfunction. Very few Jewish women gave birth. Many children were inflicted with rickets due to an inadequate intake of vitamin D. we all withered on meager food rations. Jews had to wear an armband with a blue Star of David. Later, it changed to a yellow Star of David. It was a crime if a Jew failed or rather, forgot to wear it. New rules forbade us to live, or even walk through certain sections of the town. We were ordered to take off our caps or hats and bow to any passing German. Nobody dared to raise a voice in protest. Everybody was bowed down, prostrated, and stifled. There was no other voice except the brutal German’s voice. The abominable decrees construed an attack upon the principles of a civilized society – a disgrace to humanity! Life was hardly bearable, a melancholy permeated all. However, nobody had any clue of the ominous days yet to come. In March 1940, I was shoveling snow in front of our house. I did not take off my cap when a German policeman passed by, because I had not noticed him. “I am so sorry. I am just a little Jewish kid.” I implored, but he mercilessly beat me. He could have killed me without any compunction. I was afraid to look at his face.

FROM A NAME TO A NUMBER

By Alter Wiener

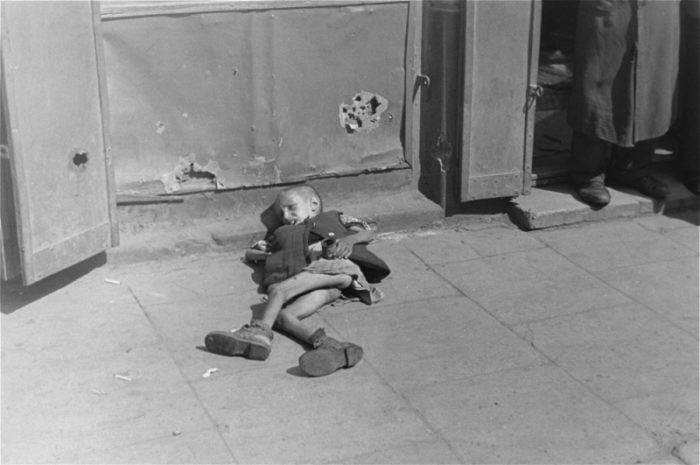

A destitute young boy lies on the pavement in the Warsaw ghetto holding a cup in his hand.

The guards marched us several kilometers down the road to Auschwitz I. En route, we passed a group of women with shaved heads and striped dresses; they were harnessed to a huge cement roller that they pulled to grade the road. Some had dilapidated shoes, some wooden clogs or sandals, and some were barefoot. The SS women guards were whipping them and yelling, “Schnell! Faster, you damn Jews!” The soles of the feet of the women without shoes had been ripped to shreds, and the rocks they walked upon were covered with their blood. The SS women were large and bursting out of their uniforms, and the contrast between them and their skeletal prisoners was striking.

BY CHANCE ALONE

By Max Eisen

We were packed tightly into the confining space [Debica, Poland] behind the brick wall, along with countless others. Breathing one another’s breath, we were shoulder to shoulder and back to back; to move an arm or leg meant dislodging someone else’s limb. To be in that attic with no possible escape should the Germans find us was a terrifying experience, as well as a supreme exercise in self-control. We were silent, as if afraid that someone was spying on us on the other side of the wall. The passage of time in the perpetual twilight was marked only by changing sounds that told us what was happening, for all of us up in that attic were by now seasoned deportation survivors. At first the ghetto was emptied of Jews. They were taken to a large pasture near the railroad tracks. We identified this stage by the people’s shrieks and the German bellowing, punctuated by bursts of gunfire; people were always brutally beaten and killed during a deportation. When the noise died down, we knew that the selections had begun. Beatings and killings were now fewer. Later, we heard the arrival of the long train of freight cars. And still later, the mournful whistle of the locomotive told us that it was evening, and that the train was starting toward Auschwitz.

THE CHOICE

By Irene Eber

In late October, he [Alois Brunner] had ordered a “Community Aktion;” many of the remaining employees of the Jewish Community [in Berlin] were to report for deportation. Some failed to appear, so Brunner had eight leaders arrested, and on December 2 all were shot.

STELLA

By Peter Wyden

I told her [barracks chief at Auschwitz] the circumstances under which I had taken my parents and my children with me, and how we had been separated from one another when we arrived at the camp. She shrugged her shoulders with an air of indifference, and told me coldly: “Well I can assure you that neither your mother, your father, nor your children are in this world any more. They were liquidated and burned the same day you arrived. I lost my family the same way; and that’s the case with all the old inmates here.” I listened, petrified. “No, no, that’s impossible,” I mumbled. This timid protest made the block chief beside herself with impatience. “Since you don’t believe me, look for yourself!” she cried, and dragged me to the door with a hysterical gesture. “You see those flames? That’s the crematory oven. It would go bad with you if you let on that you knew. Call it by the name we use: the bakery. Every time a new train arrives, the ovens fall behind in their work and the dead have to wait a day or two before they are burned. Perhaps it is your family that is being burned this moment.” When she saw that I could not utter a single word in my desperation, a profound sadness came into her voice. “First they burn those they cannot use: the children and the old people. All those whom they put on the left side of the station are sent directly to the crematory.” I stood there as though dead. I did not cry. I was almost inert lifeless. “Right after the arrival! When they put them aside? My Lord! I put my little boy on the left side. With my stupid love, I told the truth that he was not yet twelve years old. I wanted to spare him from the forced labor, and with this I killed him!”

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

For a long time, a girl who had been a student in Warsaw helped me carry corpses. We were beaten very often, for the Germans accused us of not being fast enough, and of making “funeral march” of this job. They cried, “Hurry up with those Scheiss-Stucke!” as they called the corpses, and struck us viciously. The Polish girl was dominated by one thought – love for her mother. It was her chief topic of conversation. When she spoke of her she confided, “She is hidden in the mountains. The Germans will never find her.” But one day as we entered the morgue, she broke into hysterical laughter. I had to take her out before the Germans seized her. Among the corpses she had just discovered the body of her beloved mother, whom she had thought so safe.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel

Of the four crematory units at Birkenau, two were huge and consumed enormous numbers of bodies. The other two were smaller. Each unit consisted of an oven, a vast hall, and a gas chamber. Above each rose a high chimney, which was usually fed by nine fires. The four ovens at Birkenau were heated by a total of thirty fires. Each oven had large openings. That is, there were 120 openings, into each of which three corpses could be placed at one time. That meant they could dispose of 360 corpses per operation. That was only the beginning of the Nazi “Production Schedule.” Three hundred and sixty corpses every half hour, which was all the time it took to reduce human flesh to ashes, made 720 per hour, or 17,280 corpses per twenty-four hour shift.

FIVE CHIMNEYS

By Olga Lengyel