This morning [at Plaszow] the food arrived early. As it stood for hours in the sun, it became putrefied and alive with worms. I noticed a long, white worm wiggling in my Mommy’s spoon as she lifted it to her mouth. I shrieked with horror. Mommy was startled; she looked at me with astonishment. “What happened?” “Mommy, there’s a worm on your spoon! Look, Mommy, there are hundreds of worms in your bowl! And in mine! Look!” “Nonsense! These are not worms. Eat, and leave me alone.” “But mommy, these are worms. Live worms. They crawl. Look.” I pick one of the swarming insects out of my bowl and place it on the ground. It begins crawling. Then I pick up another. It, too, begins crawling. Mommy looks at me with helpless despair. “What are you trying to do? What is your objective? Tell me, what do you want of me?” I don’t understand. I wanted to save mommy from a horrible fate: disease, or death. Or simply from the horror of swallowing worms. Instead, she is furious with me. My mother, the finicky lady who had been reluctant to eat in restaurants, and even in friends’ houses, for fear the vegetables, or hands, were not washed thoroughly enough, who baked, not only cookies and cakes, but even our daily bread at home, for fear the flour in bakery goods had not been carefully sifted, now is glaring at me. “I can’t leave this food. I am very hungry. Do you want me to die of hunger?” Her voice is beyond recognition. Her facial expression is beyond recognition as she goes on, “And there are no worms in it! Say no more of it!” As Mommy continues eating I turn my bowl over, spilling its contents on the ground, and run. I sit on a boulder at a distance, and begin to cry. My God. My dear God, is this actually happening?

I HAVE LIVED A THOUSAND YEARS

By Livia Bitton-Jackson

A group of broken souls moves slowly past our detail in blue-and-gray-striped dresses with clean, white pressed aprons. Their skeletal forms do not haunt me as badly as their bottomless eyes. We freeze for a moment of shock before returning to our work. Their knees quiver weakly, as if each step they take is their last. I shudder, surprised by the chill racing down my spine despite the warmth of the day. I have seen many things between Auschwitz and Birkenau, but never have I seen anything comparable to this. I have seen despair and hopelessness; I have seen insanity at first onset, but I have never seen a face so devoid of life. Even the dead look more alive than these walking corpses. “They are experiment victims,” the girl next to me whispers. Danka’s face pales. My hands tremble. “They torture them until they are dead or vegetables.” She turns another shovelful of dirt over. “After they are done experimenting with them, they go to the gas.”

RENA’S PROMISE

By Rena Kornreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam

Real hunger soon gripped Konigsberg…Eyes grew dull, cheeks hollow, skin turned grey and limbs were no longer round. “Mina, a beautiful strong young Swiss woman, in two months had become a wrinkled bent and haggard old lady; she had lost her morale and had to be led about like a very young child.”… Most lost their minds [at Konigsberg]. Before the snows came there was a potato patch at the end of the field and sometimes you could steal potatoes. One day a Polish woman crept there and was seen by one of the guards, who warned her to come back. “Perhaps she didn’t hear or perhaps she was partly mad. Anyway he shot her in the back and she died right there on the ground.”

RAVENSBRÜCK

By Sarah Helm

An informant in the German Army… described how this detachment had occupied another small Polish town, bringing along their wounded. The local Pharmacist and his wife, who were Jews, “worked like Trojans to help us dress the wounds,” the informant told Lochner. “We all respected the people.” The grateful soldiers assured the couple they would be protected by the German Army. Then the detachment was ordered to move on. “Even before we had time to depart, the SS were there,” he added. “A few minutes later the Jewish couple was found by one of our men with their throats slashed. The SS had killed them.”

HITLERLAND

By Andrew Nagorski

In the defense of the cold-heartedness of the Slovak women: these young women had been dragged from their homes by the Nazis two years earlier, and some told us – to our immense horror – they had been sent to the front to service the soldiers. We hadn’t wanted to believe these atrocities, but now we found out they were true. Most of them suffered through this miserable ordeal and were transported to Auschwitz once they became ill. What they must have been through, the human mind cannot grasp. Some had witnessed their friends being torn to pieces by dogs, which in those days used to be the favorite sport of the henchmen of the SS.

AS THE LILACS BLOOMED

By Anna Molnar Hegedus

The faces of the older men, the ones with families were set in deep apprehension [the first night in Auschwitz.] A middle-aged man standing near to me and Pierre gave way to tears. “Where could they be?” he asked pleadingly, as if I might have an answer. “I have a wife and a child, three years old.” He shook his head…There were religious people among us who had arrived with their large families, and they started to cry out, wail and beat their chests. They faced east and chanted Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead.

DESPERATE JOURNEY

By Freddie Knoller with John Landaw

Monotonous days rolled into weeks at the camp [Barthold]. Our bread rations decreased, and our soup rations grew more foul. My stomach, weakened by the severe attach of jaundice over a year ago, rebelled against the diet; I could eat very little…Other suffered more from heat exhaustion; it was the hottest, driest summer and fall in German history. My heart went out to those who collapsed daily in the mid-afternoon sun. They were given little mercy or relief. A pail of water might be dumped over them, followed by a stern lecture on the strength of the pure Aryan race and the weakness of us despicable Jews. With that, a pick was forced back in their hands and a gun butt drove them back into the trenches.

TRAPPED IN HITLER’S HELL

By Anita Dittman and Jan Markell

After a while, I learned that if a person in the clinic [Langinbilau] were sick more than one week, he or she was injected with kerosene. Death came a few minutes later. As time went on, many people arrived from different places. One group of several hundred people were from Holland, including youngsters ages 16 and 17 years old. Within a short period of time they became sick with dysentery. They were so sick that they did not have enough time to run to the bathroom. Instead, they defecated on the floor. We had to bring pails to clean up; chlorine was spread on the floors. For several weeks there was a terrible smell. About 20% were helpless, laying on the floor. Within a short time they died.

MEMOIRS OF A HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR: ICEK KUPERBERG

By Icek Kuperberg

If I look at a map today, I see that the distance from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz is not very great. Yet it was the longest trip I have ever taken. The train stood around, it was summer, the temperature rose. The still air smelled of sweat, urine, excrement. A whiff of panic trembled in the air… An old woman who sat next to my mother gradually fell apart: first she cried and whimpered, and I grew impatient and angry with her, because here she was adding her private disintegration to the great evil of our collective helplessness. A defense reaction: I could not face or assimilate the reality of a grown-up losing her mind before my eyes. Finally this woman pushed herself onto my mother’s lap and urinated. I still see the tense look of revulsion on my mother’s face in the slanting twilight of the car, and how she gently pushed the woman from her lap. Not brutally and without malice. At that moment my mother became a role model for me, which she generally was not. It was a pragmatic, humane gesture, like a nurse might employ to free herself from a clinging patient. I thought my mother should have been indignant, but for her the situation was beyond anger and outrage.

STILL ALIVE

By Ruth Kluger

One day, I saw something that left me shaken to my core. I heard some noises in the street, and I peeked around the corner. I saw the father of a family I knew well. This family had been butchers for generations. The Nazis also saw the family and started chasing after them. The father stopped and turned around, and one of the Gestapo raised his pistol and fired from four feet away. The German shot the man in the head, and I could see a pink and red color near his ear. But even though blood was pouring from his ears, he was still breathing. His wife went running to him, and he was still alive. “Please, please, leave him alone,” she screamed at the Germans. “He’s alive. Let him go. He’s done nothing to you.” The Germans shot her and she fell to the ground like a sack of wheat. Then their daughter came, screaming, “Look what the murderers are doing.” They shot her, and she fell backward. Then their son, a schoolmate of mine, came running up, screaming and waving his arms. They shot him. He fell in a heap. I was frightened. For the first time, I could feel deep, cold fear rush through my bones. I realized the Gestapo would return and kill others, including my family. I ran into our house and vomited in the toilet.

DEFY THE DARKNESS

By Joe Rosenblum with David Kohn

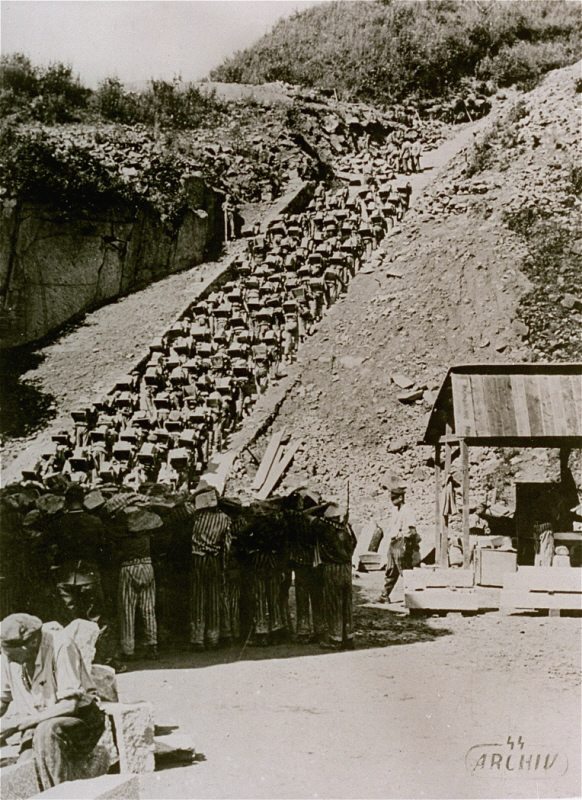

Prisoners carry large stones up the “stairs of death” (Todesstiege) from the Wiener Graben quarry at the Mauthausen concentration camp.

The platform and the nearby square were filled with corpses removed from the cars and the bodies of those shot on the spot. Oskar Berger who was brought to Treblinka on August 22, describes the scene: “As we disembarked we witnessed a horrible sight: hundreds of bodies lying all around. Piles of bundles, clothes, valises, everything mixed together. SS soldiers, Germans, and Ukrainians were standing on the roofs of barracks and firing indiscriminately into the crowd. Men, women, and children fell bleeding; the air was filled with screaming and weeping. Those not wounded by the shooting were forced through an open gate, jumping over the dead and wounded, to a square fenced with barbed wire.”

BELZEC, SOBIBOR, TREBLINKA

By Yitzhak Arad

Chil Rajchman, who worked as a barber and later in the removal of bodies, describes the state of the victims after the doors of the gas chambers had been opened: “There was a difference in the appearance of the dead from the small and from the larger gas chambers. In the small chambers death was easier and quicker. The faces often looked as if the people had fallen asleep, their eyes closed. Only the mouths of some of the gassed victims were distorted with a bloody foam visible on their lips. The bodies were covered in sweat. Before dying, people had urinated and defecated. The corpses in the larger gas chambers, where death took over, were horribly deformed, their faces all black as if burned, the bodies swollen and blue, the teeth so tightly clenched that it was literally impossible to open them and get to the gold crowns…we had sometimes to pull out the natural teeth – otherwise the mouth would not open.”

PERPETRATORS

By Guenter Lewy

“We heard the Germans and the Polish police going by. I couldn’t help wondering who they were taking this time, who they would find. Later, when it seemed safe, my sister sneaked out to see if the roundup was over. A little while later she came back and said, ‘The Germans took quite a few people.’ Then, in a very soft voice, she said, ‘Mother and Nusia are gone.’ Neither one of us cried. We just sat there…and looked at each other. You might wonder why we didn’t cry. After all, I was just a little boy of seven or eight! But by then I was already numb! I had lost so many people: an aunt one day, a cousin the next.”

THE HIDDEN CHILDREN

By Jane Marks

“Ala showed us her right hand which had a missing finger. ‘You see, Elly, from this hand they tore my baby Rochele away from me, and for screaming so much they cut off a finger. I fought for my child but they were stronger.’ She described other horrors to me – babies cut up or their backs broken and thrown into garbage cans, all in front of their crazed mothers’ eyes.”

A SMALL TOWN NEAR AUSCHWITZ

By Mary Fulbrook

One day in midsummer 1942, I was scrubbing the Zbanski stables when my brother Hymie came running in. I was shocked. Hymie never visited the farm without advance notice. His face was flushed, and was gasping for every breath. His eyes bulged. His face filled with pain. I knew I didn’t want to hear what he was going to tell me, but I faced him. “Our family has been taken to Treblinka. I escaped from the market square where they took everybody. But they took our whole family, Mother, Father, Fay, Rachel, Benny, and our nephew Harry. They pushed them into train cars filled with the smell of chemicals. They were going to push me in, too, but I ran away from the marketplace. Mother yelled, ‘Run, Hymie, run. Try to save yourself. This is it. Run to Joe.’ They were shooting after me, but I zigzagged and escaped.”

DEFY THE DARKNESS

By Joe Rosenblum with David Kohn

The German occupants began their bandits’ work in Slavuta with the persecution and destruction of the Jews. All the Jews were made to wear special armbands. They were driven out to do the heaviest physical labor and were often shot there on the spot. Shootings were carried out both in an organized manner, by the orders of the German commandant of the town of Slabuta, and in a disorganized manner – at the whim of any soldier or officer. In this way, by the close of September 1941, the Germans had killed around five thousand Jews in Slabuta. Among them were women, old people, children. Those that survived – around seven thousand people – were wiped out by the Germans through mass shootings near the water tower of a military base.

THE UNKNOWN BLACK BOOK

By Joshua Rubenstein and Ilya Altman

There were already thirty graves in the small forest. Graves of the lovingly protected daughters of thirty mothers, the cherished darlings of thirty fathers. Young lives that had been extinguished so prematurely; how many dreams of a happy future had each of them held dear? One of the girls asked me in a weak voice, the day before her death, whether she should wear a long dress at her wedding when she went home to her fiancé. They were dreaming about bridal veils, a beautiful new home, and in their eternal home, they didn’t even deserve a shroud or a coffin. Now their dreams were buried with them, and only the grim trees of this hated foreign land whispered farewell to them.

AS THE LILACS BLOOMED

By Anna Molnar Hegedus

Meanwhile, our food situation [at Auschwitz] continued at subsistence level. We learned to find worms in the soil, or swat mosquitoes, then toss them into our mouths. We’d pick up roots and leaves to fill our stomachs. I learned to peel the bark off trees while I was still moving. Personally, I liked worms and roots best. They seemed to be the most nutritious. Even so, we were always hungry. Back at the camp, we could at least get water out of rainwater barrels. Solid food, however, was hard to come by. Fortunately, nature had provided an answer, though not an easy one. The thousands of acres we worked consisted of mostly grass, and the sounds of frogs croaking after a spring or summer rain were never far from our consciousness. Of course, they disappeared in winter. I quickly learned the French Jews considered frog legs a delicacy. I saw one of them popping a live frog into his mouth and I almost vomited – until my rumbling stomach told me any food would do. The French Jew showed me how to peel off the skin, even while the frog was still alive. After I learned, it took only seconds to skin an entire frog. I could only catch the smaller ones because I was younger and had small hands. The Germans, French, and Dutch were generally bigger and older. They caught the big frogs. I also quickly learned there was no time to peel off the skin. You had to pop the frog into your mouth fast, or another prisoner would grab it from you and eat it. That happened often because many prisoners didn’t have the strength to chase the creatures. These prisoners were just waiting to grab frogs somebody else had caught.

DEFY THE DARKNESS

By Joe Rosenblum with David Kohn

So this is it. Liberation. It’s come. I am cold. The trembling in my stomach…Too much air…it’s too light. I am very tired. A middle-aged German woman approaches me. “We didn’t know anything. We had no idea. You must believe me. Did you have to work hard also?” “Yes,” I whisper. “At your age, it must’ve been difficult.” At my age. What does she mean? “We didn’t get enough to eat. Because of starvation. Not because of my age.” “I meant, it must have been harder for the older people.” For older people? “How old do you think I am?” She looks at me uncertainly. “Sixty? Sixty-two?” “Sixty? I am fourteen. Fourteen years old.” She gives a little shriek and makes the sign of the cross. In horror and disbelief she walks away.

I HAVE LIVED A THOUSAND YEARS

By Livia Bitton-Jackson

2 May 1945, Four a.m. Five a.m. Six [the day of liberation]… We step into dawn’s light nervously, wondering what new trick this is that our captors are playing. There is no roll call. There is no one but us in camp, just one lone guard still in the watchtower. Not one SS woman, no wardress, no camp elder anywhere to be seen. We stand on the camp road gazing at the guard in the watchtower, wondering what to do. He is the only thing between us and freedom, and his gun is aimed directly at us. I look at my watch. It’s ten o’clock. How long must we wait here when freedom is laughing just on the other side of these gates? A mother and daughter decide they were hungry enough to brave getting to the pile of potatoes. They run across camp toward the only food left. A gunshot rips through the girl’s heart. She collapses. Her mother screams, rending her clothes and cursing God. No one dares to go comfort her. A second shot rips her throat out.

RENA’S PROMISE

By Rena Kornreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam

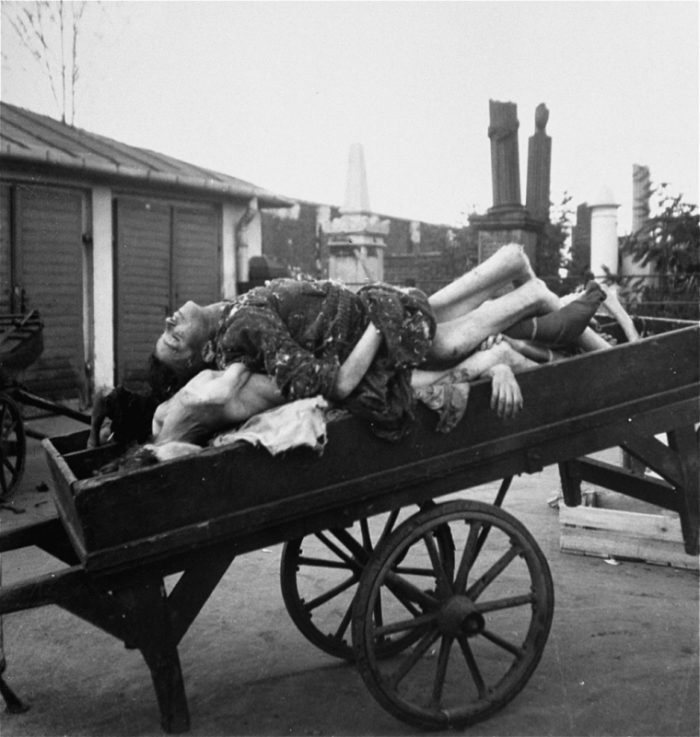

Emaciated bodies piled on a cart await burial in the Jewish cemetery in the Warsaw ghetto.